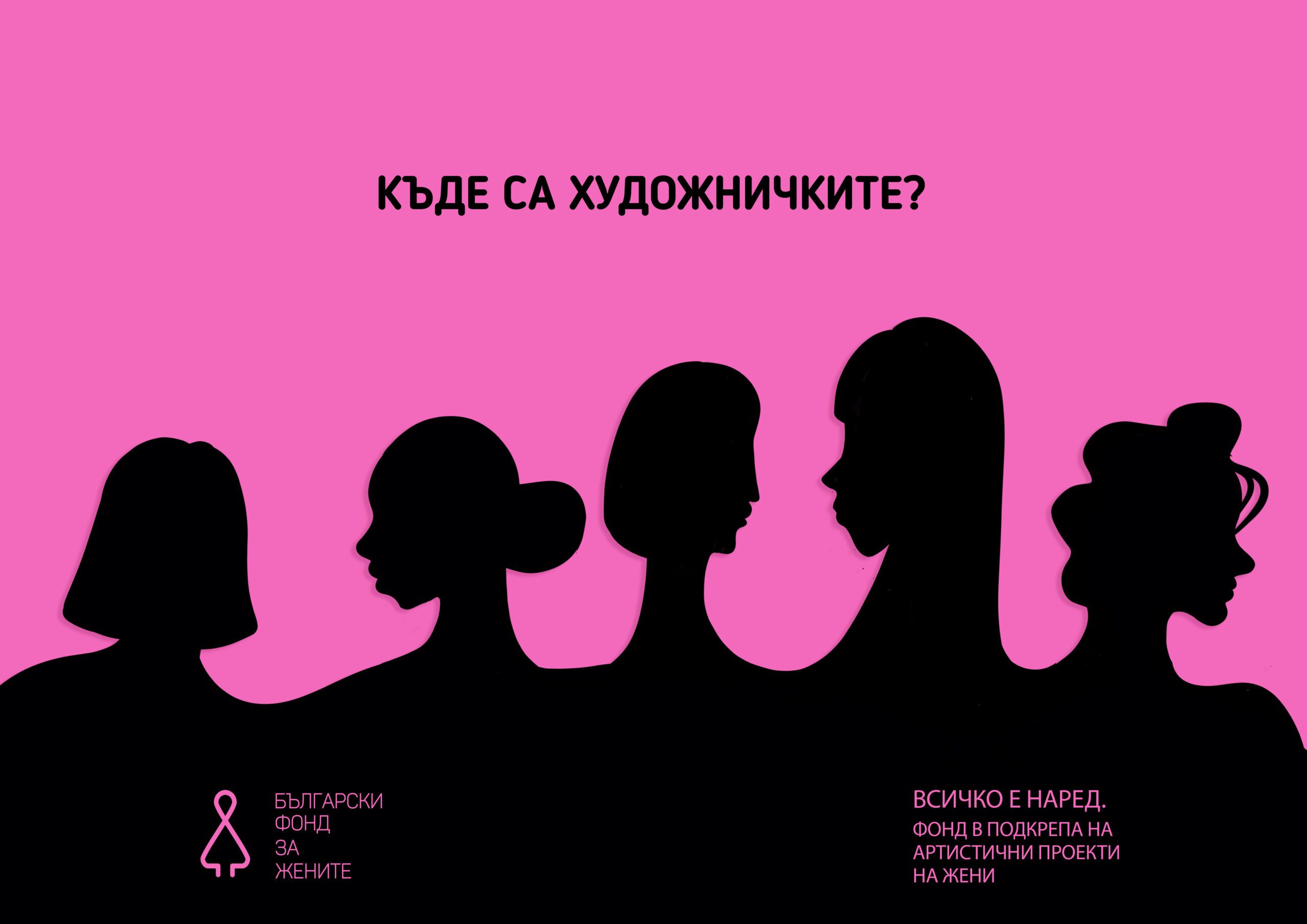

This legendary question asked the Guerrilla Girls, an anonymous group of feminist female artists devoted to fighting sexism and racism in the art world in 1989. Whether it is still standing today and how has the situation changed in the art scene in the last 30 years we’ll find out in the interview with Frida Kahlo, one of the Collective’s founders. To remain anonymous, members wear gorilla masks and use pseudonyms that refer to great historic female artists. The collective is widely known for using culture-jamming tactics relying on mass media formats such as billboards, bus-ads, and posters to challenge discrimination and corruption.

The interview with Frida Kahlo was taken in January 2018 by Svetla Baeva, within the Fulbright Program in the United States in connection with a study of effective advocacy campaigns. We publish it with the author’s permission in the context of the BFW Women’s Artist Fund.

In this Fund’s context, the Bulgarian Fund for women organizes a call for proposals for women’s artistic projects. More information about it and how to apply you can find by following this link: //bgfundforwomen.org/bg/2019/05/22/konkurs-za-artistichni-proekti-na-jeni/

You’ve been asked this a lot, but how did you start out in 1985?

I think the issues of race and gender have been somewhat acknowledged in the art world but when we first started, they were not important at all. Everyone thought that the cream was always rising to the top and the fact that there were no women or artists of color in museums was because they weren’t good enough. I don’t think anyone would argue now with our point which is that you can’t write a history of a culture without all the voices of the culture in history.

We started out in 1985 and the impetus was an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City which was touted as the most important survey of international art possible. There were nearly 200 artists in the show but only 13 women and even fewer artists of color. The curator made a very arrogant statement that anyone who wasn’t in the show should rethink his career. Just the use of that pronoun told us that we are not even in the running.

We went to a protest at the museum that was organized by a group of feminist academics. It was a very standard protest with placards and chants and all. Kathe Kollwitz, one of the founding members, and I then realized that the people going in and out of the museum were not interested in what we had to say. They really believed that the art world was a meritocracy. We realized that standing outside a museum complaining wasn’t transformative. So we decided that day that we would try to figure out some new way to address the situation.

We got together with a bunch of other women. There are a lot of arguments about how many we were at the very beginning. We don’t even remember. Everything was done very organically and very quickly. Each one of us has a different story about it. We had an early meeting where we decided that we wanted to be anonymous because the art world is such an upper-class place. The idea of being freedom fighters was just tantalizing and calling ourselves girls would make even feminists sit up. We wanted everyone to listen.

Then we started doing in-your-face posters that named names of people who participated in a system that ignored women. We did poster after poster. We did a poster at galleries, we did a poster at museum shows, we did a poster about art critics, we did a poster about male artists, left-wing male artists who allowed their work to be shown at galleries that didn’t show women at all. Everyone started listening and arguing and also wondering who we were.

You started your first campaign for female representation in art over 32 years ago, what would you say is the situation now?

What we didn’t realize is that tokenism, not just with regards to women and gender equality, but tokenism in terms of marginalized groups in general, is the first way the system tries to change things. Museums and galleries will have one woman artist and one artist of color and think that the problem is solved when it is really a richer idea than that. The art world, because it is so hypercapitalist, is about money and having winners. Afew winners and many, many losers. So, it needs a genius. Of all of the artists working in a certain style, the field can only reward one or two of them. We are also thinking more about how American museums, most of which are private institutions, are often run by people who are involved in the business of art. We are asking the larger question — is that ethical?

Has your protesting/complaining changed since starting out? Is the context different?

The context has changed. We have learned a lot about what works and doesn’t work. We have done more than a hundred projects. People know a few of them very well but they don’t know all the stuff in between that tells the story of our thinking and how our thinking evolved. I would say that the context has changed in that big money has more of a role in the art world so that has changed our target. It used to be straight misogyny, racism, and sexism. Now it is also corruption and all the things that go with it. And capitalism. We live in an economy where the market rules. Our feeling is that profitability and quality do not always go hand in hand. Many decisions at museums reflect the values of their donors over the values of the people they are supposed to represent. European museums are not so extreme. They are often run by the state and do not have such a robust involvement in the art market, although that is changing. They are under pressure to adopt the American model.

We used to put up posters on the street around the galleries because that was our audience. Now the audience is much larger than that. The internet makes all sorts of things more possible. We can get to millions of people all over the world on the internet. We’ve also been doing something that we never imagined that we would even be given the opportunity to do. Museums have invited us to come in and do projects critical of their collections and acquisitions programs. We’ve organized initiatives in Whitechapel gallery, Tate Modern, Kestner Gesellschaft Gallery, Ludwig Museum, Van Gogh Museum. We will be doing something in Sweden and at the booth of the Asian Art Archives at Art Basel Hong Kong. This opens us up to all kinds of criticism that maybe we’ve sold out or been co-opted. We are really careful when we accept these invitations and we accept them with the freedom to do whatever we want. Usually, they come from well intentioned people inside the institutions who want us to be critical. They want to change their institutions. However, a single person can’t change an institution. It is a big ship to turn around.

What issues do you currently try to tackle?

White supremacy, patriarchy and corruption and how they get all entwined. As we look at the top of the ladder of success, it gets more and more white and more and more male. We are looking at exclusion in a larger sense. It is not always conscious and it is not always overt. And it gets institutionalized.

What is creative activism for you?

It is what we do. We just decided that there had to be a new way of transforming people’s thinking. It wasn’t about pointing at something and saying that this is bad, I’m angry about it. It was about twisting an issue around, presenting it as maybe a riddle or a conundrum or some unanswered question. And then hitting back with some statistics that would change someone’s mind. We do things for people who don’t agree with us. We try to figure out a way to get them to think about an issue rather than merely saying that we are angry about it. We would think up of a provocative headline like: “Do Women Have to Be Naked to Get Into the Met Museum?” Then the statistics follow: “In the modern art sections of the museum, only 5% of the artists are women but 85% of the nudes are female.” If you look at our work, you’ll see that that is an overriding aspect. We will say something outrageous to get someone’s attention and to get them thinking about the issue. Then we will back it up with some information that will try to get them to change their minds.

What campaign tactics/media techniques do you use?

We started out with posters on the street. We’ve done banners and exhibitions. We’ve written five books. We’ve done huge public projects. We did an exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, which was entirely based on a questionnaire sent to 383 directors in Europe about their exhibitions programme and collections. We are starting to do animations that play on a stream. We did an animation for the Minneapolis Institute for the Arts, the Ludwig Museum and the Van Gogh Museum. We have expanded and realized that technology has created many other formats for ways to get our message out.

According to you, what are the basic campaign components?

We have to think about the people who disagree with us. How can we reach them? It makes you feel good to sing to the choir because everyone loves and supports you but we really want to do something that cannot be forgotten by someone who disagrees with us.

What role do you think art can play in campaigning?

Art is about what you’d never thought about before or you never imagined could happen. It doesn’t go away. It hangs around and haunts you. That’s the power of art. Frankly, there are a lot of art students now who don’t necessarily want to join the world of galleries and museums and making art for the art market. They want to really use their creative talents and their communication skills to make a better world. Demonstrations are more interesting visually than they ever were before. That is creative complaining.

From your perspective of having worked with activists in other countries, what advice would you give to women’s rights activists today, particularly in Eastern Europe, who are having a hard time putting issues on the agenda?

We realized that there are many feminisms. Not everyone’s feminism works in other parts of the world. It is always a response to a context, to the powers that be. We realized that the situation for women is more difficult in other countries than in the United States. I would be a little cautious about telling anyone what to do because we live in a country that if a protest is unpleasant, it just gets ignored. But there are countries in which protest gets punished. All I would say is know your audience. Be clever. Be self-protective. And don’t give up. If something doesn’t work, try it again. If it works, try it again as well. But know your audience and know the situation that you are in.

Interview: Svetla Baeva

Photos: Guerrilla Girls