Galya’s life was turned upside down when she lost her husband in a car accident and was left to care for her two children, aged 8 and 10, alone and homeless. This could be yet another family falling through the cracks had it not been for the timely intervention of the Women’s Roma Association “Hayachi”, which the woman’s relatives had heard about from a TV report on joint initiatives with UNICEF.

Our longtime partners, Muzeyam Ali (Chair), Maria Nikolova (Vice-Chair) and Nurten Dzhevdzhetova (nurse, health mediator and member of the association) shared their insights on how their community, which is often wronged and discriminated against when not completely erased from public discourse, responds to the needs of the most vulnerable.

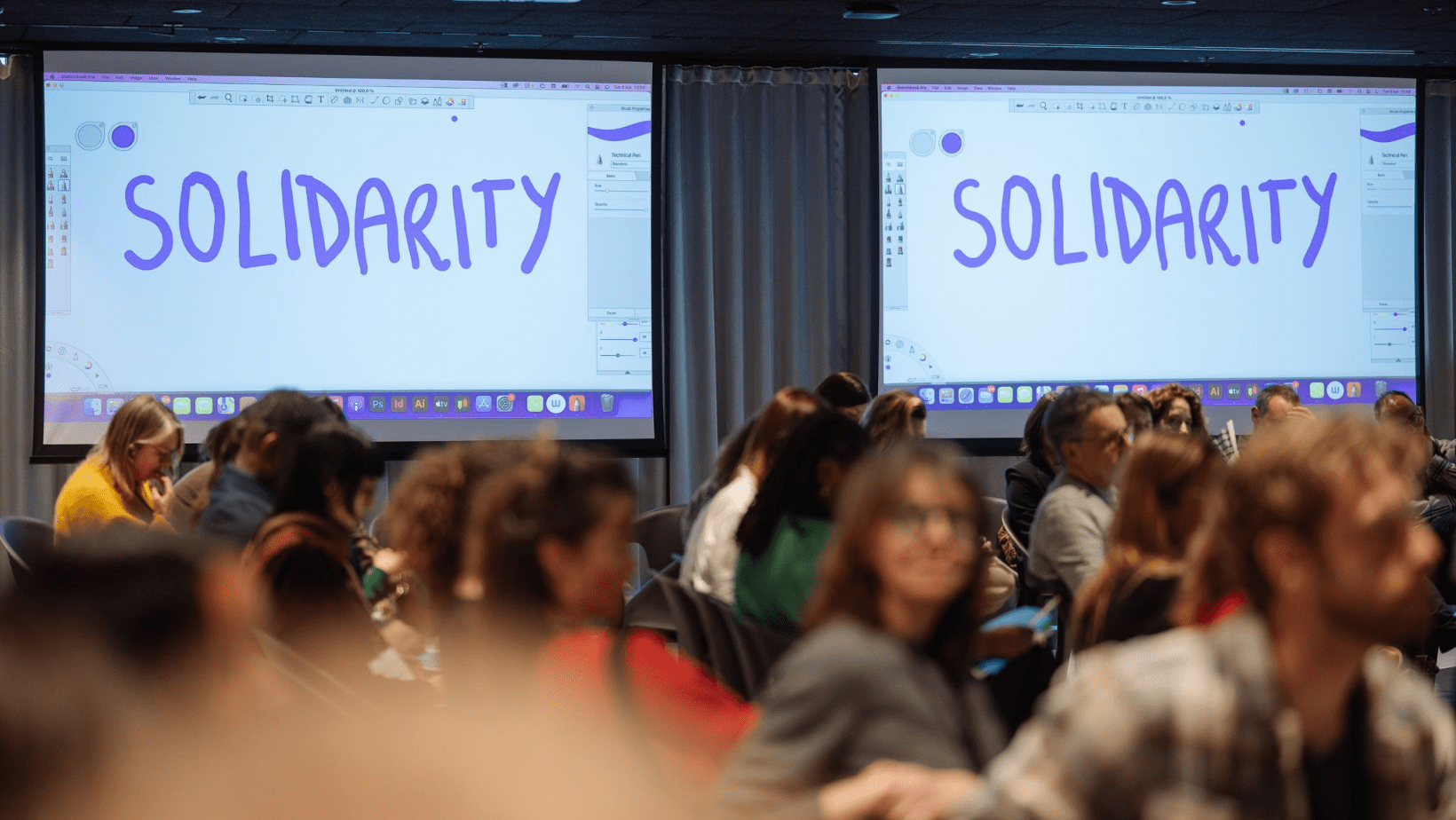

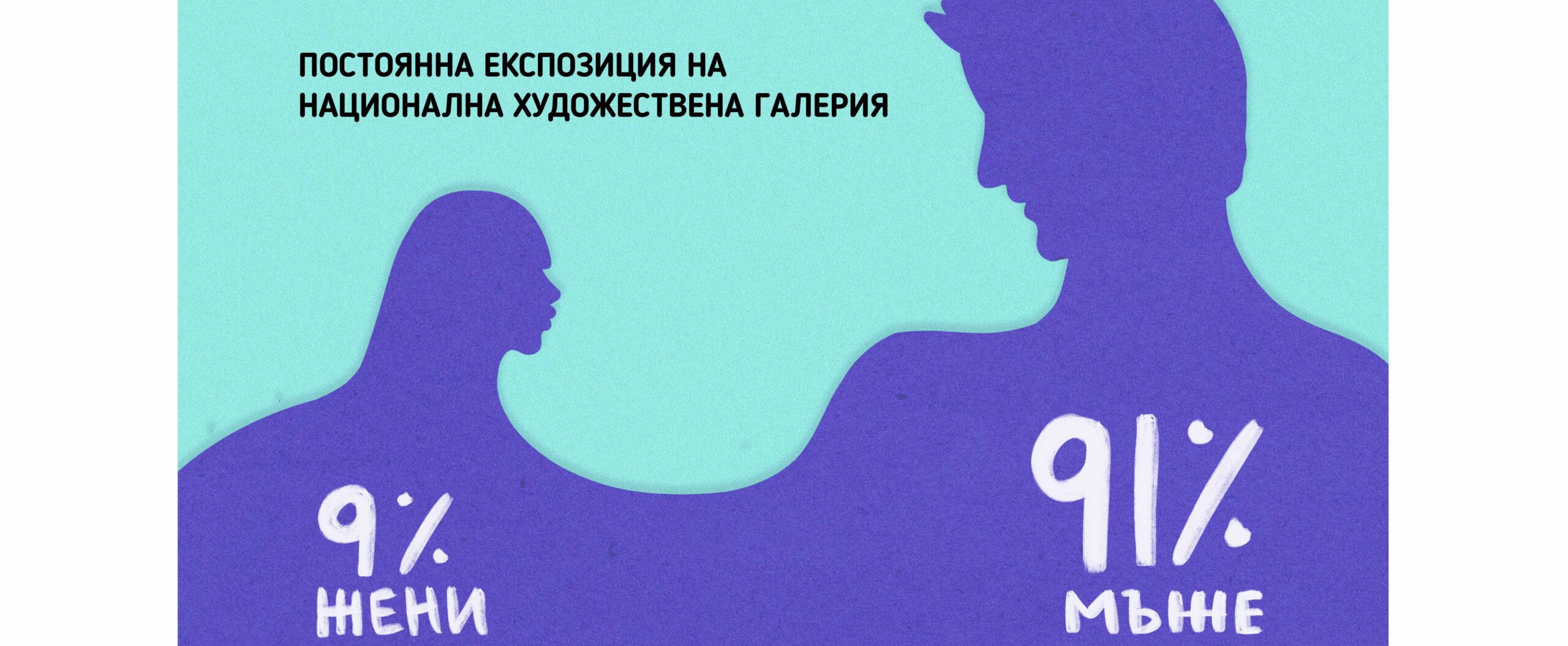

Underpinning those happy endings are the more than twenty years of field expertise members of the association have under their belt and the tight bonds of mutual trust and solidarity in the community itself. Nurten stresses that proper needs assessment is a vital first step in working with vulnerable groups. Due to their gender, ethnicity, or class, among other characteristics, the former are both more likely to need social services and less likely to access them than the average citizen. When Nurten and other Hayachi volunteers first met Galya, the latter was destitute; not only had she lost the roof over her head but could rely on no support from relatives in raising the children – despite having a high school diploma and a steady income.

Hayachi’s team acted swiftly. They organized a fundraising campaign and solicited material donations towards the renovation of the home that now allows Galya to be a mother to her kids. The call for help spread through word of mouth and social media networks, where younger volunteers of the organization shared pictures and brief reports of the work done. Muzeyam Ali, chair, emphasized that the donors were often ordinary people from the poor parts of town, who have little to spare, yet help unselfishly. Other donors include local businesses that contribute in-kind donations, having seen first-hand the gradual transformations Hayachi has brought about in the most marginalized communities.

In passing, they mention the detail that Galya and several other single parents receiving support from Hayachi are ethnic Bulgarians while insisting that the organization does not divide people by skin colour or religion. Instead, their shared values, tested by the demands of fieldwork, unite their multiethnic team. If they are not looking for public recognition of all their initiatives, that is because, in the words of the Muzeyam, they are trying to “help without humiliating the other person” or turning suffering into a sensation. These stories are worth telling, however, as they undermine the pernicious stereotype of Roma’s dependence on the state prevalent in public discourse in Bulgaria.

Moreover, they are not an exception but indicative of Hayachi’s preventive efforts toward the well-being of children, young people and women. “If we didn’t work with women, who are making a difference in the community, we wouldn’t be who we are today”, the team said. Knowing the problems of the most vulnerable first-hand, the organization intervenes to correct seemingly insignificant shortcomings of state and municipal institutions, which would otherwise fester into more intractable problems for the community. Insufficient social services for new mothers and newborns in small towns and rural areas are a salient example. The so-called “one-time assistance”, a legal entitlement of all new mothers in the country, is often delayed or insignificant, especially for pre-term babies. Maria emphasizes that the additional prenatal packages provided by the Association in a timely manner are often the only thing that prevents the abandonment of newborns. At the same time, mothers and mothers-in-law in the community are responsible not only for ensuring the physical well-being of children but also for passing on customs and values.

Hayachi’s many years of experience suggest that traditions while affirming identity, can pose risks for adolescents. The team stressed that they are working to change attitudes, “not by imposing changes, but by offering alternatives.” A specialist like Nurten, a medical professional and community leader, can suggest how risky practices, such as swaddling or “salting” newborns, can be modified instead of suppressing and eradicating Roma identity. Hayachi’s work, on the other hand, suggests that young people of exemplary character and merits also influence attitudes in the community. It is no incident that the Association measures its achievements by the number of young university graduates in its ranks and the accomplishments of volunteer girls who develop professionally, despite communal expectations to marry and bear children at a young age.

Beyond field work, the Association also contributes to social change through advocacy at the municipal and national levels. In 2004, the informal mutual aid network around the Muzeyam and Maria was institutionalized with the help of the BFW to formally establish “Hayachi”. Since then, the organization has involved the local government in at least a few significant initiatives, the latest of which is the creation of municipal family planning funds. Nurten said this was virtually the only way for vulnerable, often uninsured women to gain access to long-term contraception, which, in turn, reduced criminal abortions and unsupervised pregnancies. The initiative is a clear example of how, unlike social services, which cover immediate basic needs, long-term efforts towards social change aim to restore the autonomy and personal dignity of those affected and involve them in the solution.

Once approved by the Novi Pazar municipal council, the same model is making its way to Nikola Kozlevo, Kaspichan, Devnya, and Maria is optimistic that the initiative will reach even more local communities in the future. Systemic changes like subsidies for kindergartens and dairy kitchens require that civic associations spare no effort and persevere in the face of institutional inertia or prejudice. Successful implementation presupposes sensitivity to the needs of marginalized communities and an understanding of what measures work in the long run. Under these conditions, social services are perceived not as a personal privilege but as a reasonable investment in the wider community. Muzeyam emphasizes: “We insist that the children go to the nursery and kindergarten very early; this is how they learn the Bulgarian language and get a solid routine, which is a springboard for their further development”.

When we talked about the aspirations of the Association, the leadership was unanimous that they strive for closer cooperation with other CSOs and a gradual introduction of locally successful policies at the national level. Accurate problem appraisal, often neglected or biased in political and media discourse, proves to be a critical prerequisite for the above and one of the essential contributions of civil society. To cite but one example, as part of the informal collective RavniBG, coordinated by BFW, Hayachi is mapping illegal residential buildings in marginalized neighbourhoods of Novi Pazar. Thanks to the trust they enjoy in the community, the team has found that only 155 of the 306 surveyed properties have a notary deed, and the owners of the rest are at constant risk. In addition, Hayachi has examined attitudes towards potential solutions among those directly affected and relayed those insights to the local government, which does not have the same access and direct expertise – thus serving as a bridge between the state and its invisible citizens.

BFW is particularly proud to provide flexible support, from guidance on institutionalizing informal initiatives to capacity-building resources to organizations such as Hayachi. In this way, the latter serve their mission more resiliently and can respond in a timely manner to the real needs of the communities they know better than anyone. This support is only proportional to the grantees’ dedication and hard work. As Muzeyam stressed, “we were born here; we live here; we work here. For us, there are no days off, no working hours.”