Though the law explicitly prohibits discrimination based on sexual orientation, Bulgaria remains one of the last EU countries that has neither legalized same-sex marriage nor recognized any form of an intimate relationship between same-sex partners. As a result, members of the LGBTI community remain “second-hand” citizens, deprived of about 300 rights – from joint adoption of children and rights of inheritance to free movement with their families within the Union.

The legal program of the Youth LGBT organization Deystvie, supported by the Bulgarian Fund for Women, is one of the few citizen-led initiatives purposefully addressing the cumbersome bureaucracy and lack of political will to protect and promote LGBTI + rights in the country. We talked to legal experts Veneta Limberova and Elitsa Atanasova from Deystvie about the distinctive difficulties of strategic litigation. Lilia Hadjiivanova, an activist, organizer of an online community for LGBTI+ Bulgarians in New York, and a member of the Advisory Board shared why such efforts resonate so profoundly with compatriots abroad.

A legal case is “strategic” when it has the “vision and potential” to change national legislation from the inside out. For non-lawyers, it can seem flabbergasting how time-consuming and difficult it is to litigate one and how far-reaching the ramifications of winning could be. Until all possibilities at the national level are exhausted, and a certain case reaches international courts such as the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), “three, five, seven years …” could go by. When she is questioned by non-experts (“But why these time-consuming cases?”), Veneta Limberova insists, “There is no other way!” Partly because the legislative process in Bulgaria is ponderous, and partly because the state does not consistently implement already established rules and principles – European or Constitutional – due to a lack of expertise or incomplete guidelines for their practical application. The latter omissions are amendable if the administration is proactive and says to itself, in Limberova’s words, “we are missing something here now.” But human and LGBTI + rights seem to be a “hot potato” for the Bulgarian National Assembly and institutions. Hence, putting pressure on the state to take measures by complying with the decision of an international body turns out to be the only constructive approach.

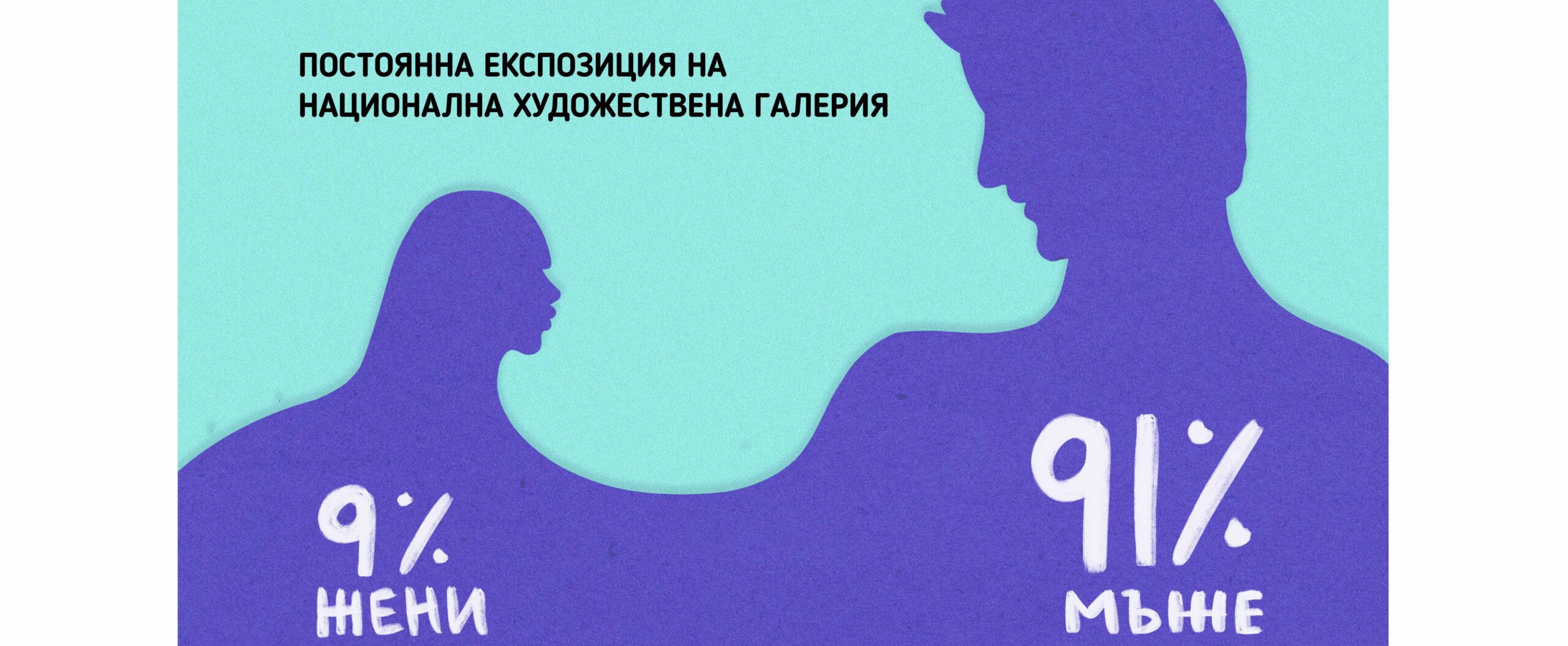

The association’s legal experts and lawyers are forthright about the importance and limitations of the legal program. Its significance goes far beyond the struggle for equality of the LGBTI + community as it fosters a model for holding public institutions to account and empowering citizens to exercise their rights which is transferable to other social movements in the country, such as the women’s and environmental ones. But reaching a strategic case requires an energetic and resourceful organization which has the capacity to run multiple initiatives and partnerships at once.

One of those strategic goals is raising the awareness of the community itself about its rights and available means of mobilization, which the LEAD project of “Deystvie” with LGBTI + youth and activists aspires to do. On the other hand, uncertainty and time lag make strategic litigation “extremely inefficient in terms of resources and time”, according to Limberova. Finally, Bulgaria has become “notorious” for losing in the ECHR. “Bulgaria constantly pays compensations to litigants, which costs taxpayers a lot, but does not implement… Why?” According to members of the association, the missing link is a robust civil society that has developed sufficient expertise and self-awareness to be both a watchdog and a valuable source of expertise for the state administration.

For those seeking legal aid from Deystvie, the stakes are often their human dignity and the integrity of their families, and only then – the foundations of liberal society. Limberova emphasizes that their program eventually had to offer psychological support in parallel with legal assistance because these are not just cases but “living people”: “We usually aim to work with more than one couple at once and put the plaintiffs in touch. So that the burden, the personal burden of going to trial, can be shared.” In addition to the uncertainty, the disgraceful condescension of officials, and the long wait, many couples confront a dilemma of whether to publicize their battles.

Lilia Babulkova and Darina Koilova, or simply Lily and Dari, who have been trying to register their British marriage for about ten years, initially refused to share their tribulations with the media. And when they did, in Lily’s words, they discovered that “complete strangers” could hate them “openly, ardently.” In this context, some plaintiffs view the cases not only as a means to regain some of their autonomy and declare, “This is my family!”, but also as a form of micro-activism that gives heart to like-minded people. However, others acknowledge that despite their commitment to the cause and the satisfaction of seemingly insignificant victories (such as a shared last name), emigration is always on the agenda as an alternative to indefinitely deferred equity at home.

For many members of the LGBTI + community, Deystvie is emblematic of their struggle for true belonging to Bulgaria. This is, even more, the case for some expatriates who would like to return, physically or metaphorically. Lilia Hadjiivanova has lived in New York for years but met the association’s team last summer when she and her wife Terry began contemplating how to raise their future children: “We want our child to have a Bulgarian birth certificate, to speak Bulgarian, to keep in touch with our friends in Plovdiv “, Lili asserted. The break with her biological parents, who cut off all contact when she came out, motivated her to create a community for LGBTI + Bulgarians in New York, recently featured in the Washington Post. One’s “chosen family”, as Lily often calls it, is a vital link to the roots for other members of the group as well, whether their blood relatives have severed ties or not: “Very few people understand both experiences and how they intersect – being an immigrant from Eastern Europe and being gay at the same time,” Lily said. She was equally amazed and moved by the rapid growth of her community and its ongoing engagement with social and political processes in Bulgaria.

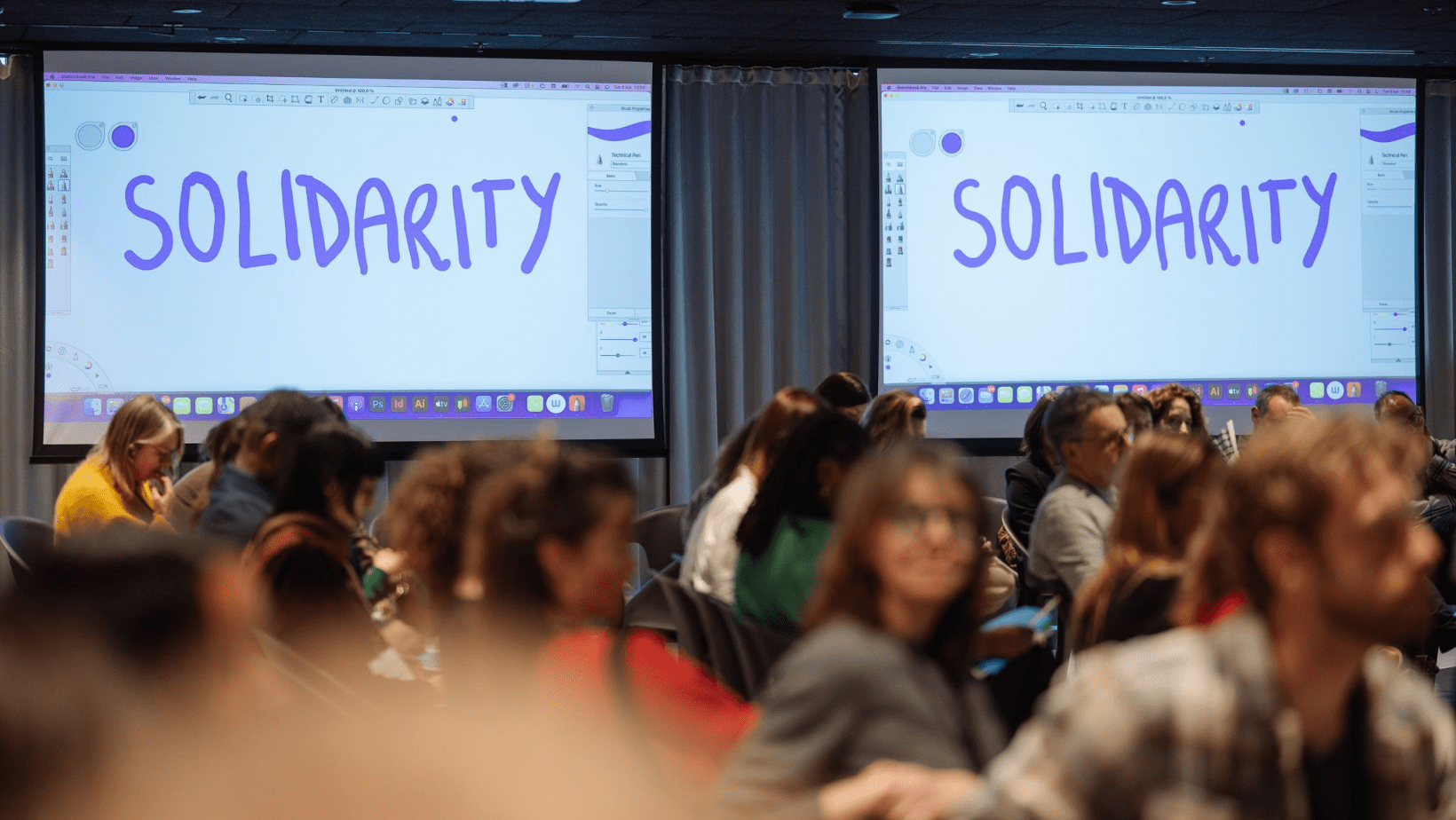

By virtue of its specific positionality – as an “exile” whose way back is blocked by obsolete legislation, on the one hand, and as the bearer of different experiences and civic consciousness, on the other hand, the Bulgarian LGBTI + diaspora is an invaluable ally of Deystvie. According to Limberova, the LGBTI + rights movement and the entire civil society in Bulgaria have a lot to learn from ex-pats who have experienced first-hand how the public supports various causes, has a mature donor culture, and organizes events and initiatives at the grassroots level. A commitment to mutual learning and solidarity brings together allies like Lili on the Advisory Board: “We have a member who works at the UN; another is straight ally and mother of a transgender child struggling for legal recognition of her transition… These are different perspectives and experiences that enrich our work.” She believes supporters of the cause who have settled down in more accepting and liberal societies have both the freedom and a distinctive responsibility to mobilize resources and expertise, albeit remotely.

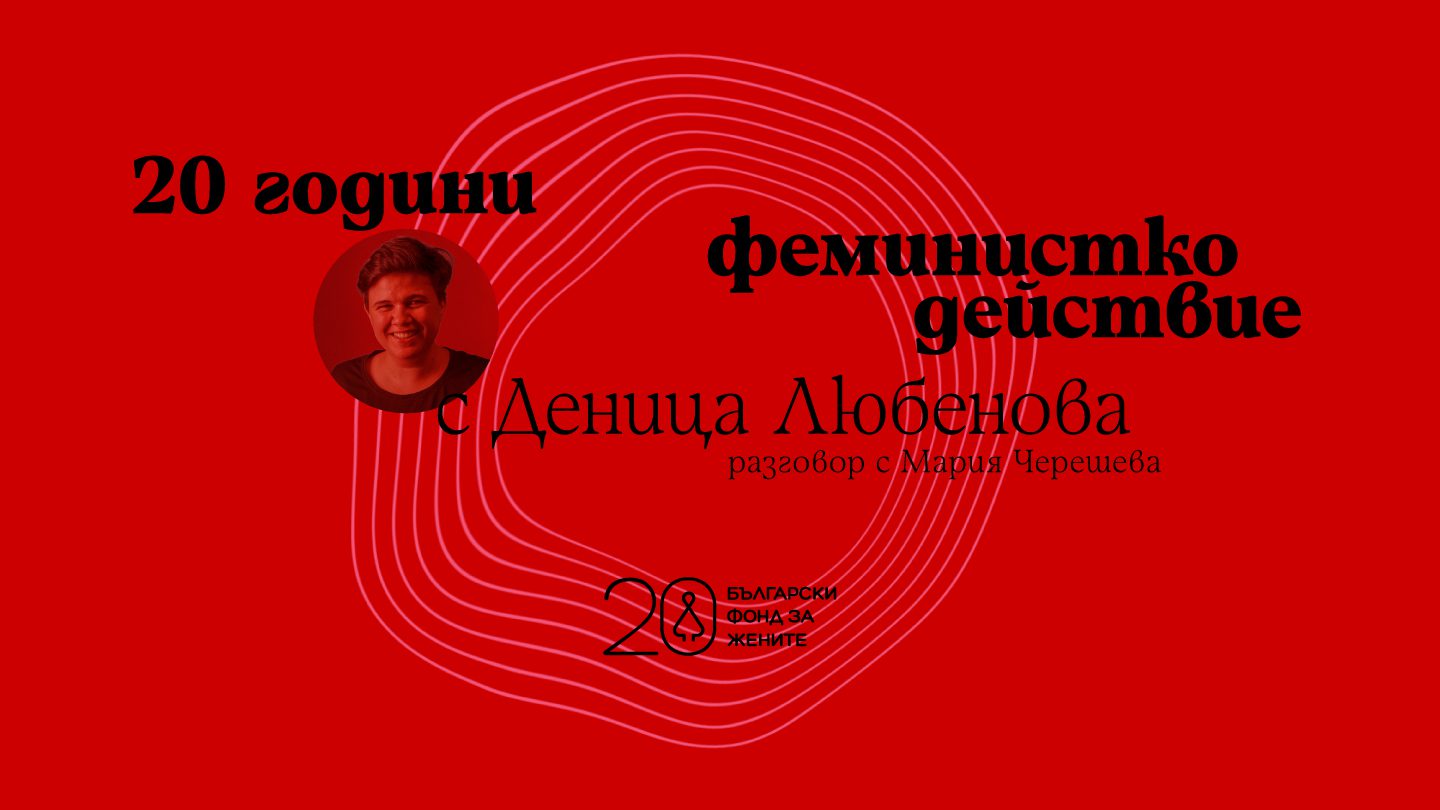

Our conversations took place on the eve of the historic victory of legal expert Veneta Limberova and lawyer Denitsa Lyubenova in the case of baby Sarah. On May 17, 2022, a Bulgarian court ruled that the Sofia Municipality must issue a birth certificate in which both the Bulgarian and the English mother of Sarah are recognized legally as parents. The outcome vindicated Limberova’s prediction the first children to receive such rights will be those born abroad, paving the way for a “family for all” in Bulgaria. It also justifies her lasting conviction that a strong civil society that knows how to push the levers of the law can perform “feats of courage.”