Behind many public causes lie deeply personal stories. However, we rarely hear about them, because human rights defenders prefer to talk about the battles they are fighting, not about themselves. I have had dozens—maybe even hundreds—of conversations with people working on socially significant topics. Yet, I have rarely thought about how little I actually know about them.

That is why, with some trepidation, I asked Denitsa Lyubenova—a lawyer whose work I have been following closely for about a decade—to share her personal path to the cause of the youth LGBTI organization “Deystvie” that she leads.

“Is it OK to ask about this?” I wondered. But it was too late.

The Path to Yourself

“A difficult question,” Denitsa answered. Then she spoke. And when lawyer Lyubenova speaks, it is worth listening—after all, the Court of Justice of the EU in Luxembourg, in a grand panel, heard her.

Denitsa was born in the late 1980s in Vidin—“perhaps one of the poorest places in Europe, not only in Bulgaria.” She spent her childhood and adolescence in a traditional, heteronormative society, typical of every small Bulgarian town. There, the topic of LGBT and non-traditional sexual orientations is not part of the conversation. It does not exist, either at home or at school.

Although these early teenage years do not evoke bad memories for her, Denitsa is categorical about one thing:

“I have always wondered, what the hell is wrong with me?”

She found an answer to this question only when she moved to Sofia to study and watched an interview with some of the first LGBTI activists in our country—Aksiniya Gencheva and Desi Petrova, members of the Gemini organization. She describes the moment of enlightenment as follows: “It felt like being struck by lightning.”

A lot of reading and research into what it means to be a lesbian followed. She went through her own difficult, slow path to self-realization, and a revelation came over time. Unfortunately, her father’s death preceded this moment.

“He was the closest to me. And I never told him about my sexual orientation or the difficulties I was going through,” says Denitsa Lyubenova.

“In fact, the fact that I could not share this with the person closest to me made me talk more about this topic and advocate for the rights of LGBTI people in Bulgaria.”

Thus, “Deystvie” was born—from the meeting of several young people who decided to speak openly about who they are. They raised money for registration by organizing a music festival.

It All Starts… on Heels

We now know where the “youthful” in the full name of “Deystvie” comes from. However, how did the organization, founded by several young people in their early twenties, reach the stage of conducting cases of strategic importance for the entire European Union?

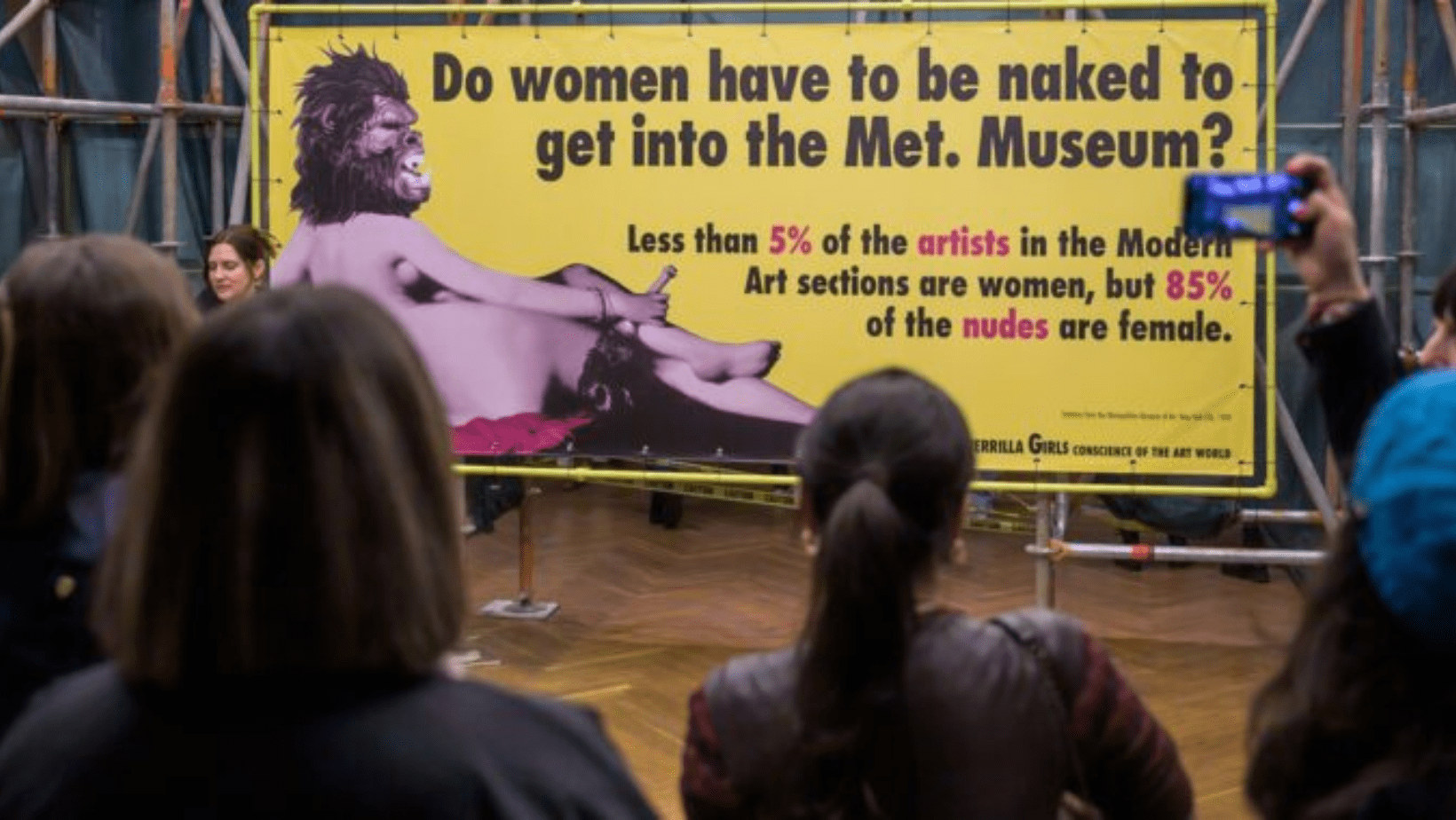

The answer is: with many protests, for all kinds of causes. The first one Denitsa remembers was for women’s rights. It was held under the motto “Walk a kilometer in her shoes.”

“We were all at those protests. Many of the boys in “Deystvie” wore high heels and walked along Vitoshka with them.” With these same girls and boys, they protested against corruption, against concrete, for the preservation of the Pirin Nature Park, and in support of people with disabilities.

Even then, they felt that the difficulties of LGBTI people were not strictly specific to their marginalized community, but were actually deeply embedded state problems—problems of a society in which hatred for anyone different had been instilled.

On One Side of the “Barricade”

Meanwhile, attacks on the civil sector have become more frequent since 2018, including attacks on cultural events of the LGBTI+ community, the hysteria surrounding the Istanbul Convention, the Strategy for the Child, and culminating with the adoption of anti-LGBT+ legislation in the summer of 2024. Perfectly coordinated actions caused harm, affecting numerous social groups. Not only the “usual suspects” were targeted, but also hundreds of teachers and academics who dared to express their dissatisfaction.

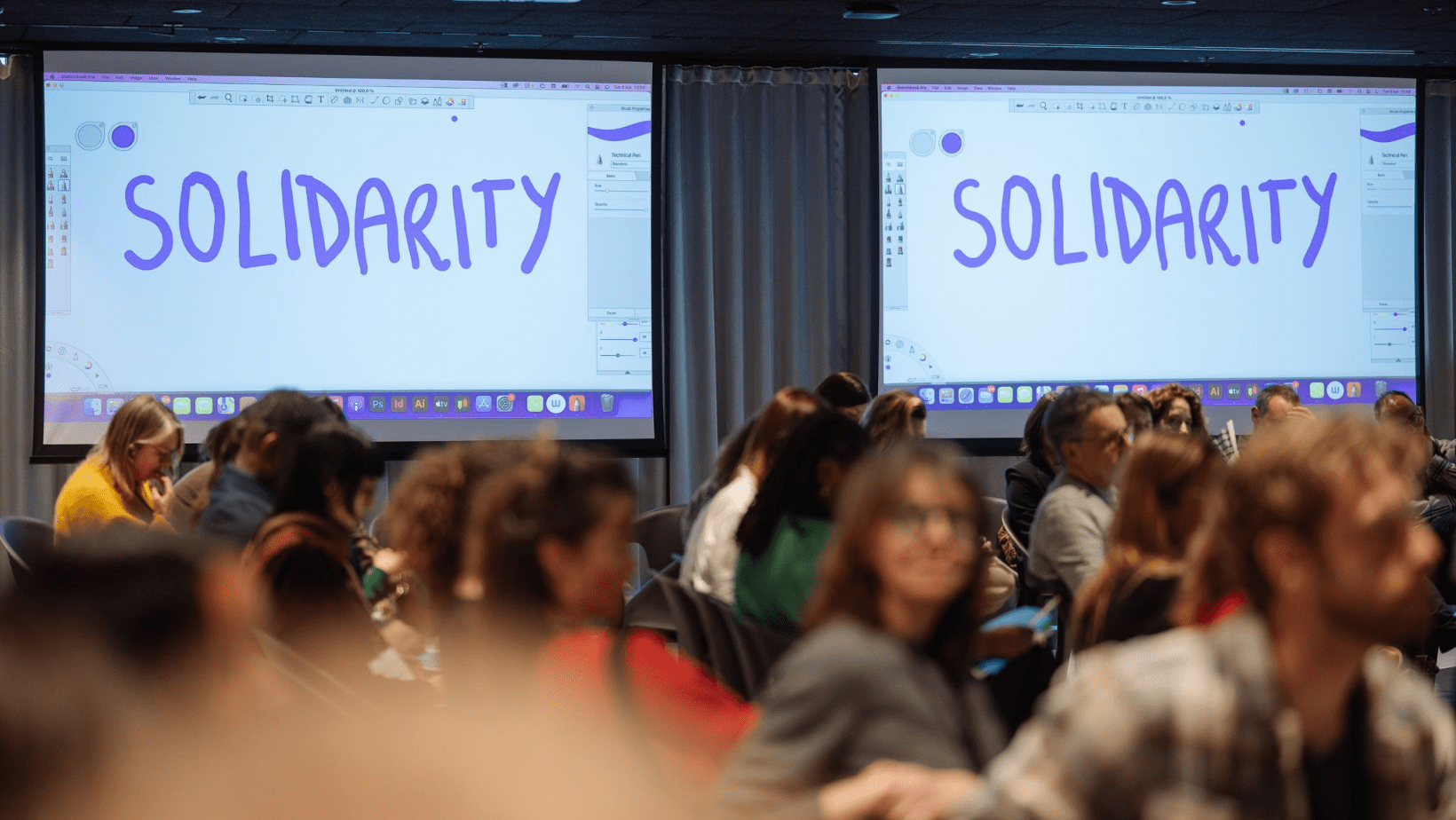

And so something new happened: civil society organizations not only started talking to each other but also began speaking with one voice, Denitsa believes.

“We cannot talk about a democratic state and the rule of law if we do not first address the debate on human rights,” she is categorical.

“I don’t know how we understood that we were on the same side of history. Maybe it was a process. It was certainly a process.”

What Are the Grants For?

It’s important to note that the conversation with Denitsa Lyubenova took place months before the new US President Donald Trump and his close tech billionaire Elon Musk put an end to the US development agency USAID. This decision put the topic of grant funding in the public spotlight, with recipients of foreign funds being the target of accusations and criticism, regardless of their purpose or origin. It is also worth mentioning that the Bulgarian Fund for Women is one of the largest donors of project funding in the country, supporting dozens of civil society organizations and feminist collectives nationwide.

The youth LGBTI organization “Deystvie” has not only implemented several important projects with the help of the BFW, but is also among the recipients of administrative funding for its activities. Denitsa Lyubenova does not hide this and explains to the audience how she uses the funds she receives.

“There’s no way we can require a non-governmental organization to provide opinions on outrageous bills that have currently entered the plenary hall, to organize events, or to carry out its main activities… in our case, this includes providing pro bono legal assistance and consultations to LGBTI+ individuals… and to do all of this pro bono,” she explains.

“We operate with public funds. And operating with public funds requires absolute transparency. If you don’t have transparency, at the first inspection, your organization will simply no longer exist,” adds the lawyer.

The EU Is Changing, but Not Us

Undoubtedly, the story with which Denitsa Lyubenova and “Deystvie” gained wide popularity outside LGBTI circles is that of baby Sara—a child with two mothers, Kalina and Jane, who are still fighting for their daughter to receive Bulgarian citizenship. Sara was born in Spain and is listed on the birth certificate with two mothers—a formulation that the Bulgarian state does not recognize in its national legislation. But should it recognize the laws of other EU countries that guarantee equal rights for same-sex families? An important question that Adv. Lyubenova is addressing.

On December 14, 2021, the Court of Justice of the European Union ruled that the Bulgarian authorities are obliged to issue an identity card or passport to Sara, certifying her citizenship and indicating her surname according to the birth certificate drawn up by the Spanish authorities. This decision is of significant importance for the development of European law and affects over 100,000 families in Europe who find themselves in a similar legal paradox.

“As a result of the ruling by the Court of Justice of the EU, a series of legislative initiatives by the European Parliament have been launched for the so-called regulation on the recognition of birth certificates for children born across borders,” says Denitsa, who is leading the case in Luxembourg.

Some member states are not waiting for the new European law, which is still under discussion, and are changing their domestic legislation to recognize birth certificates issued by other EU countries. The first is Germany, followed by even countries such as Poland and Romania, which are not known for their wide recognition of LGBTI rights.

But the Bulgarian authorities, who are the recipients of the decision from the European judges, continue to refuse to implement it. The Pancharevo district of Sofia Municipality does not recognize EU legislation, even though it has supremacy over national law.

“What was most scandalous in the case of baby Sara is that the whole of Europe, in general, recognized the consequences of the decision of the EU court,” the lawyer commented.

But she and her team are not giving up—a case has already been filed with the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, and a request has been made to the EU to initiate criminal proceedings against Bulgaria for violating EU law.

While institutions at both the national and international levels continue to pass the ball, Sara is no longer a baby. For now, the little girl remains stateless, but despite this, Kalina and Jane already have a second child. Like her sister, this child has no citizenship, which means she cannot travel to see her relatives in Bulgaria, nor does she have proper access to education or healthcare.

“We cannot afford to judge some people for deciding to express their love for each other by having children,” says Denitsa.

“The question is not whether she will have citizenship. She will have citizenship. The question is whether she will be Bulgarian or Spanish. I am actually betting more on it being Spanish,” she adds.

Denitsa does not hide the fact that this family has an advantage over many other same-sex couples—they do not live in Bulgaria.

An Open-Ended Battle for Rights

СHundreds of others, however, remain here and are trying to live their lives “bypassing Bulgarian reality.” This is not always possible—a 2018 study by “Deystvie” shows that due to the impossibility of recognizing same-sex couples’ relationships, they are deprived of over 300 rights. Their children, who grow up here among us, are also deprived of rights. If a child from a same-sex family loses their biological or adoptive parent, they face the real danger of being taken away by their other parent. This is not a hypothesis—similar situations have already occurred in Bulgaria.

That is why Denitsa and her like-minded colleagues do not stop conducting cases, training institutions in the country—including the prosecutor’s office and the Ministry of Interior—to recognize and protect the rights of LGBTI+ people, working with administrations and universities. She does not hide that they have achieved a lot of success but also that they encounter hatred at every step of the way.

“Hatred in the courtroom, ridicule, hatred from the legislator, hatred from the municipality, misunderstanding from everyone. I think there has been no real progress in Bulgarian society regarding the acceptance of LGBTI people,” she admits bitterly.

This leads to burnout among many human rights advocates in our country. How does she cope?

With exclusion. Intervals of time without communication with anyone. Connection with nature. Time in the mountains. And preserving the hope that in 20 years, organizations like “Deystvie” will no longer be needed.

“I sincerely hope that our society will have grown so much and the law will be so reformed that there will be no need for organizations that have to monitor every step of the institutions,” Denitsa concludes.