Zhivka Valiavicharska is an art historian, researcher, educator, and curator, and an Associate Professor of Political and Social Theory at Pratt Institute, New York. She earned degrees in Art History from the National Academy of Art in Sofia and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago; completed her PhD at the University of California, Berkeley; worked as the Marjorie Sussman Curatorial Fellow at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago; and specialized in and taught social theory at the University of Chicago.

Valiavicharska has extensive teaching experience in the fields of visual studies and social and political theory. She is the author of numerous studies related to feminism, postcolonial theory, and the social, cultural, and visual histories of Bulgaria and Eastern Europe in the 20th century. She works in the sphere of contemporary art.

What is the significance of the Guerrilla Girls’ work in the context of the Bulgarian artistic scene?

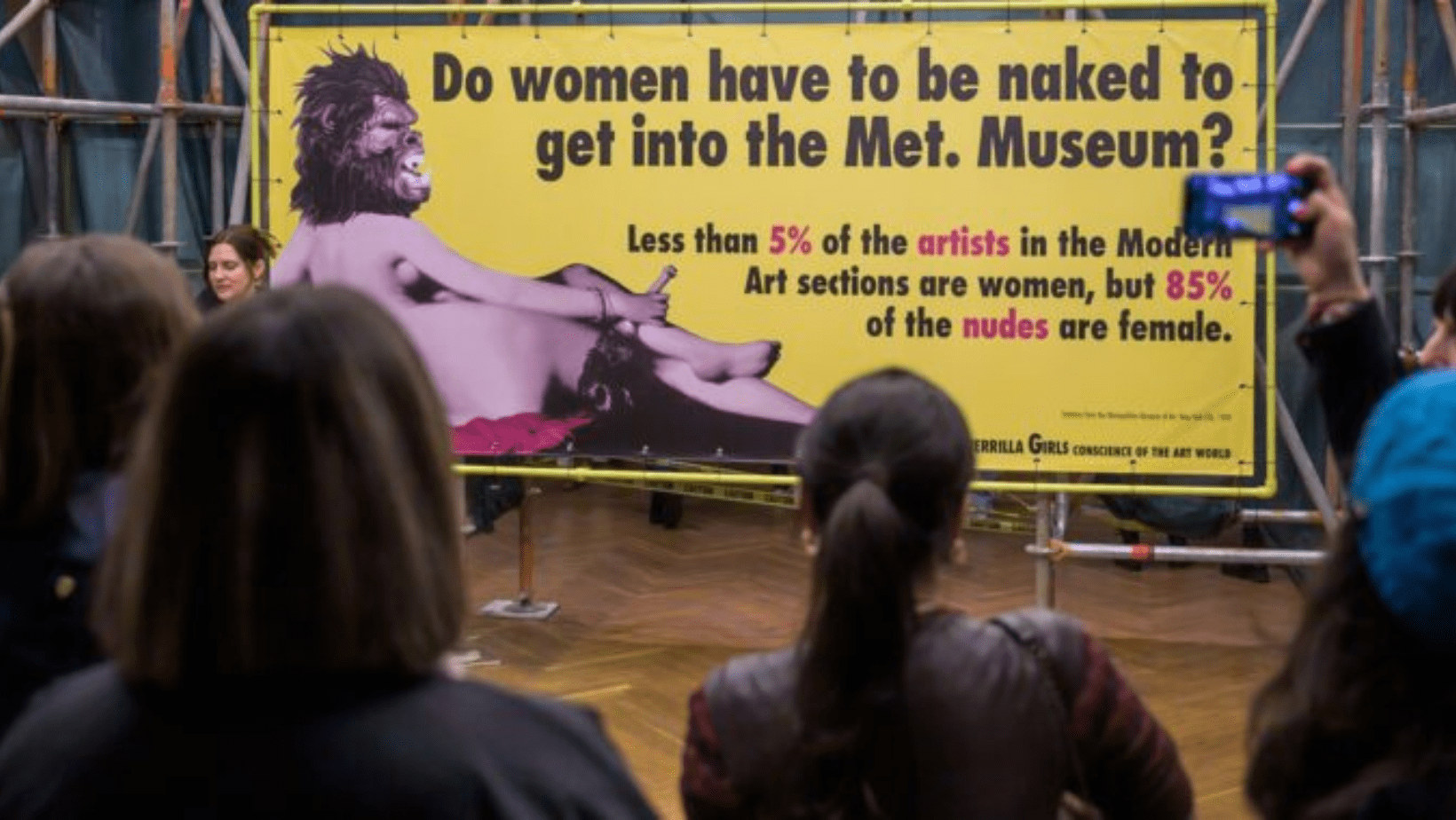

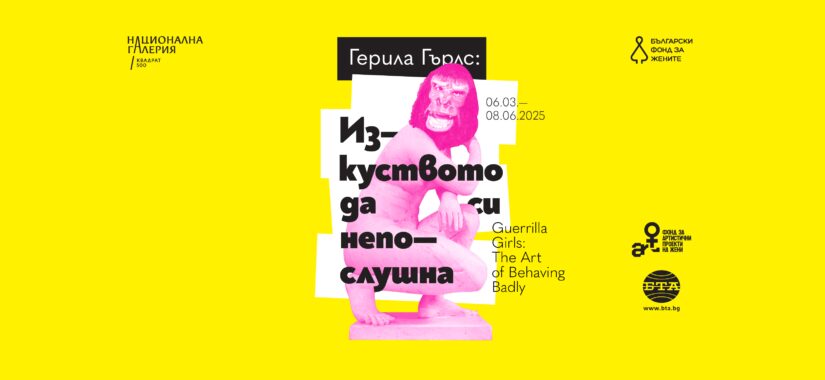

Congratulations on the exhibition—I look forward to seeing it, even if only in the final weeks of its run. As I am writing from New York City, I am holding in my hands the Guerrilla Girls’ recently published catalogue The Art of Behaving Badly. To see their work from 1985 to 2020 brought together in one volume is not only inspiring but also humbling. Their strategies—bold, flexible, inventive, and always socially engaged—intervene directly in public life: on facades, streets, and squares, as well as inside the very institutions they critique.

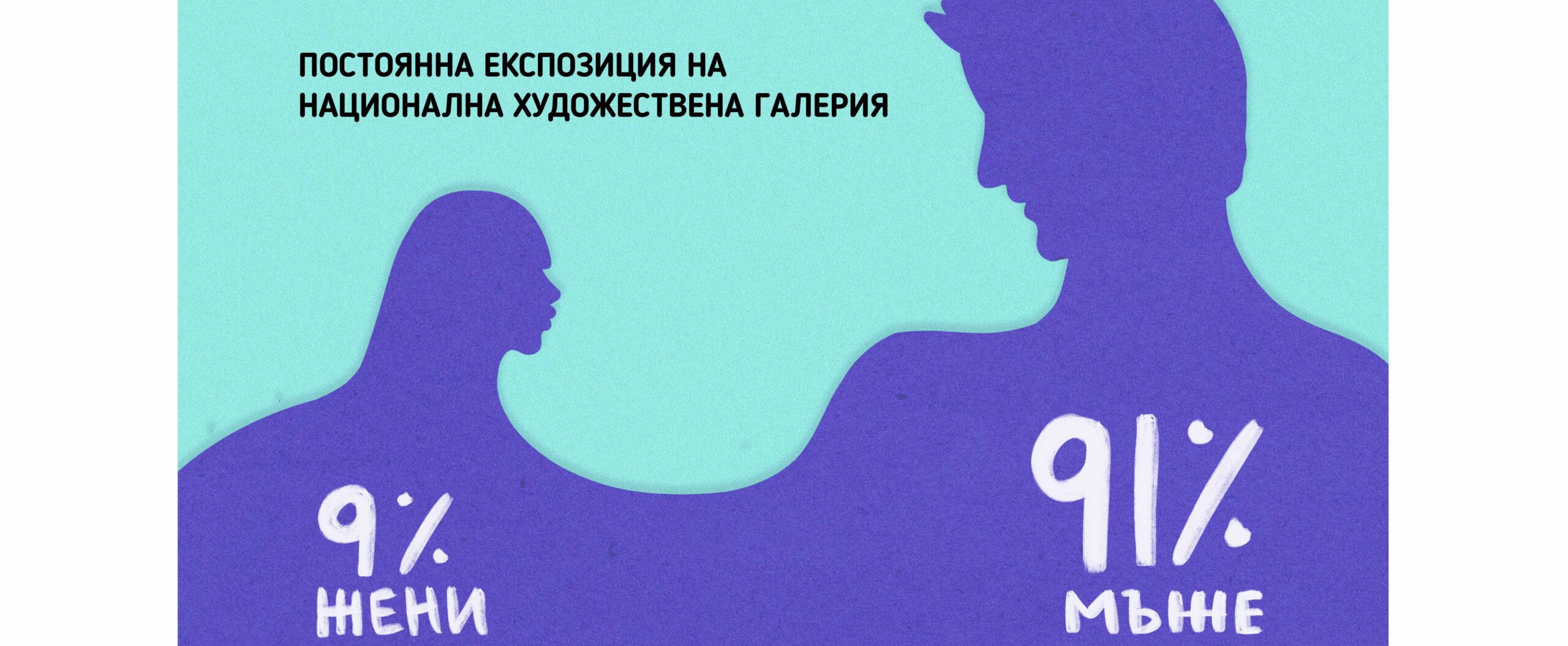

In the Bulgarian context, we have a strong need for feminist critique of the infrastructures and practices in the field of visual arts — including museums, their collections, and exhibitions, institutional practices, as well as the histories of art — its narratives, and the concepts we use. All this, not only in a sense of what percentage of “women” are present in the collections, in the administration, in art history books, etc. The critical approaches of intersectional feminism are necessary to examine how patriarchal understandings, machismo, racism, ethnophobia, homophobia, orientalization, the othering of marginalized communities, and other problems are present, often unconsciously, in the content of art, in its histories, categories, institutional practices, and museum exhibitions.

But we should not forget that the Bulgarian and East European contexts are very different from that of the United States, and any analysis must be attuned to the specificity of this context and of our history. “Women” in Bulgarian art is a theme that is strongly represented during the socialist period, and women artists have a strong presence in the arts from this period — thanks to the emancipatory policies of socialism, even if they had contradictory effects. As a result, we have a picture that is difficult to compare with the North American and West European contexts. For example, comparative studies such as that of Kristen Ghodsee (Second World, Second Sex, translated into Bulgarian by Valentina Mitkova and Natalia Afeyan, and published by Iztok-Zapad, 2020) highly appreciate the achievements of women in Bulgarian society during socialism and show how progressive our society was in this regard — compared to the inequalities and discrimination in the United States, as well as the radically different problems that women faced and fought for in the North American conditions and in the feminist movements in the West.

If you could include one work of Bulgarian art in a conversation with the work of the Guerrilla Girls, what would it be and why?

Every work — whether historical or contemporary — requires a multi-layered critical analysis, which the approaches of intersectional feminism offer. In a sense, this is a perpetual project that should never have an end: through visual analysis, critique of structural conditions, and careful contextual-historical research, we must critically read — again and again — the presence and absence of women and marginalized communities in our permanent exhibitions, in established narratives of history, and in institutional practices.

We should consider not only their absence, but also the ways in which they are present — whether they fit into problematic frames that other, romanticize, or exoticize them; whether they reproduce stereotypes, patriarchal understandings, and sexism; whether they reinforce their unequal place in society — or, on the contrary, construct images that open up opportunities for meaningful participation and contribution. Any work, exhibition, or constructed history — regardless of whether it concerns the past or the present — is subject to such analysis and rethinking, even when its content is not directly related to these themes.

Of course, we immediately think of the “female nude” theme in Bulgarian art since the dawn of academic art at the end of the 19th century — the woman as an object and a “muse” of the male artist, as well as the many representations and images of women seen through the “gaze” of the male artist. Last summer, on the occasion of the exhibition Re-/evolution of Women: Changing Roles at the Vaska Emanuilova Gallery, curated by Galina Dekova and Galina Dimitrova, it was mentioned in a conversation with colleagues how the “female nude” after a certain absence, reappeared with a new force in Bulgarian art of the 1970s — alongside themes such as the woman-mother, femininity, and other “traditional” representations of women. This can be seen as part of the pro-natalist politics of the period and its logic in which women became the central object of the biopolitics of socialist state power.

These are only general outlines of themes and issues that require precise research and visual analysis — especially in terms of how they relate to tendencies in art from the same period.

Why is art created by women and other marginalized communities important for society and artistic circles? Has the access of these groups to the Bulgarian scene changed, and in what way?

Art has the potential to make a profound impact on society on many levels. A seemingly innocuous image in a public setting can deeply affect viewers and shape our perceptions. Art created by women and other marginalized communities is particularly significant for many reasons: it gives these communities voice and visibility in the public sphere, provides opportunities for self-representation, and opens space for the critique of dominant forms, for multiple perspectives and alternative visions. In short, it is essential for building a more democratic and just society.

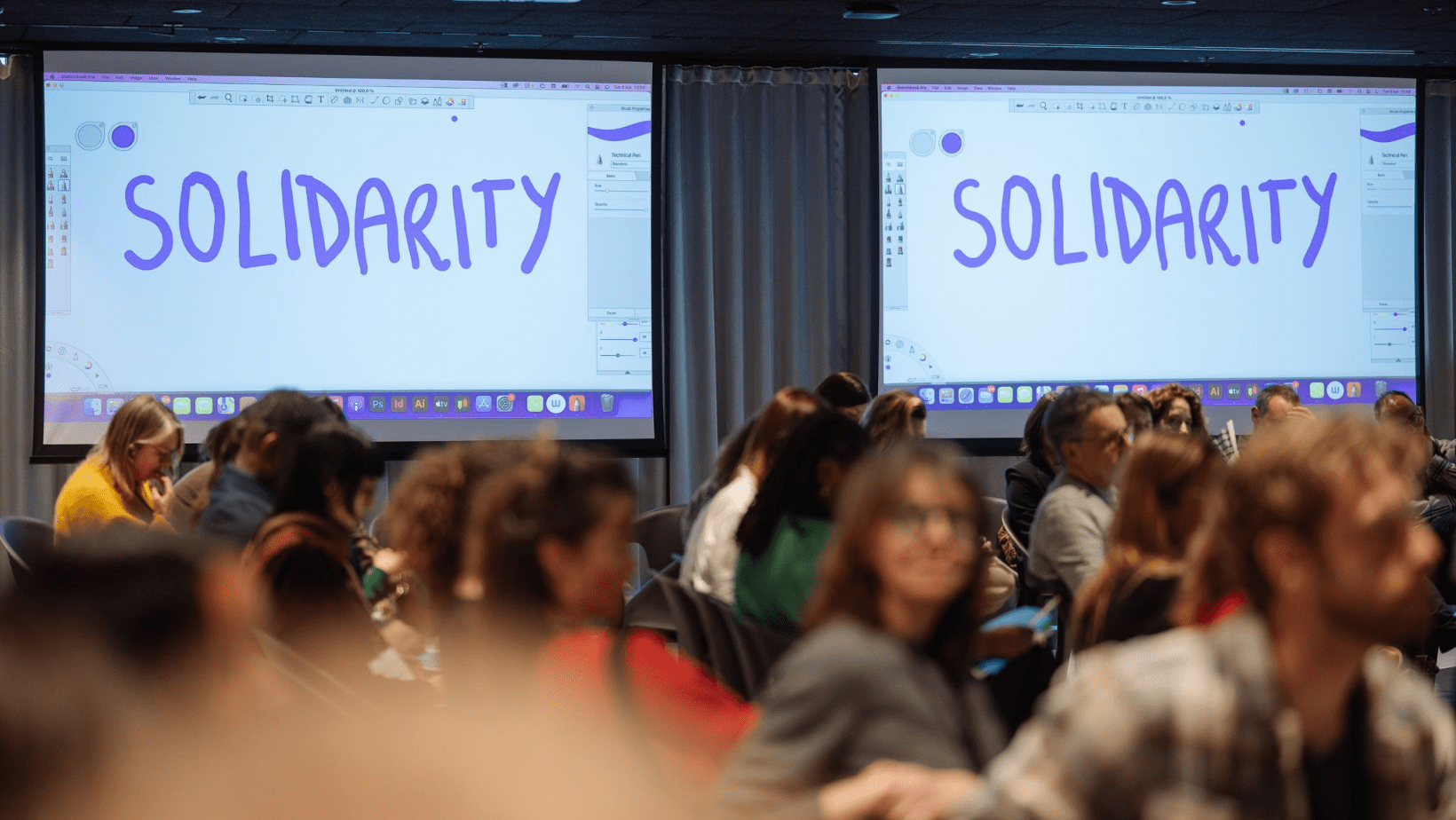

The Art of Behaving Badly continues through June 8, 2025, at the National Gallery / Kvadrat 500. The exhibition is part of the multi-year initiative of the Bulgarian Fund for Women, titled “Fund for Artistic Projects by Women Artists.”