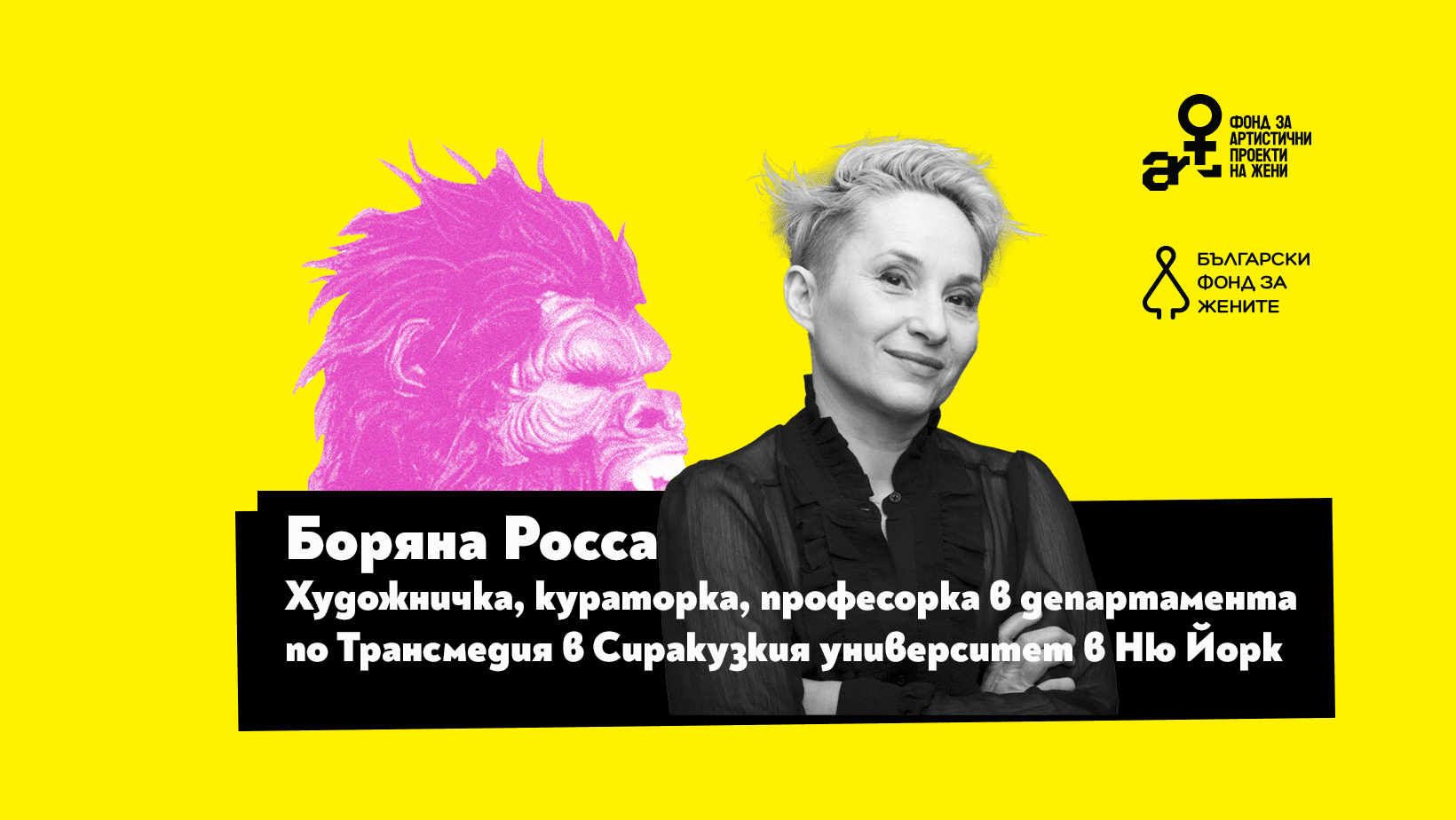

Boryana Rossa is an artist and curator. She received her PhD and MFA in Digital Arts from Rensselaer University, Troy, NY (2012), and an MFA in Mural Painting from the National Academy of Art in Sofia. She is currently a professor in the Department of Transmedia at Syracuse University, New York. Since 2012, she has been co-director of the Sofia Queer Forum alongside philosopher Stanimir Panayotov.

In 2019, Rossa participated in the first edition of the Bulgarian Fund for Women’s Women Artists Project Fund with her project Diversion: Women in Bulgarian Cinema. She was also one of the eleven artists selected in the 2020 edition, Everything is (Just) Fine.

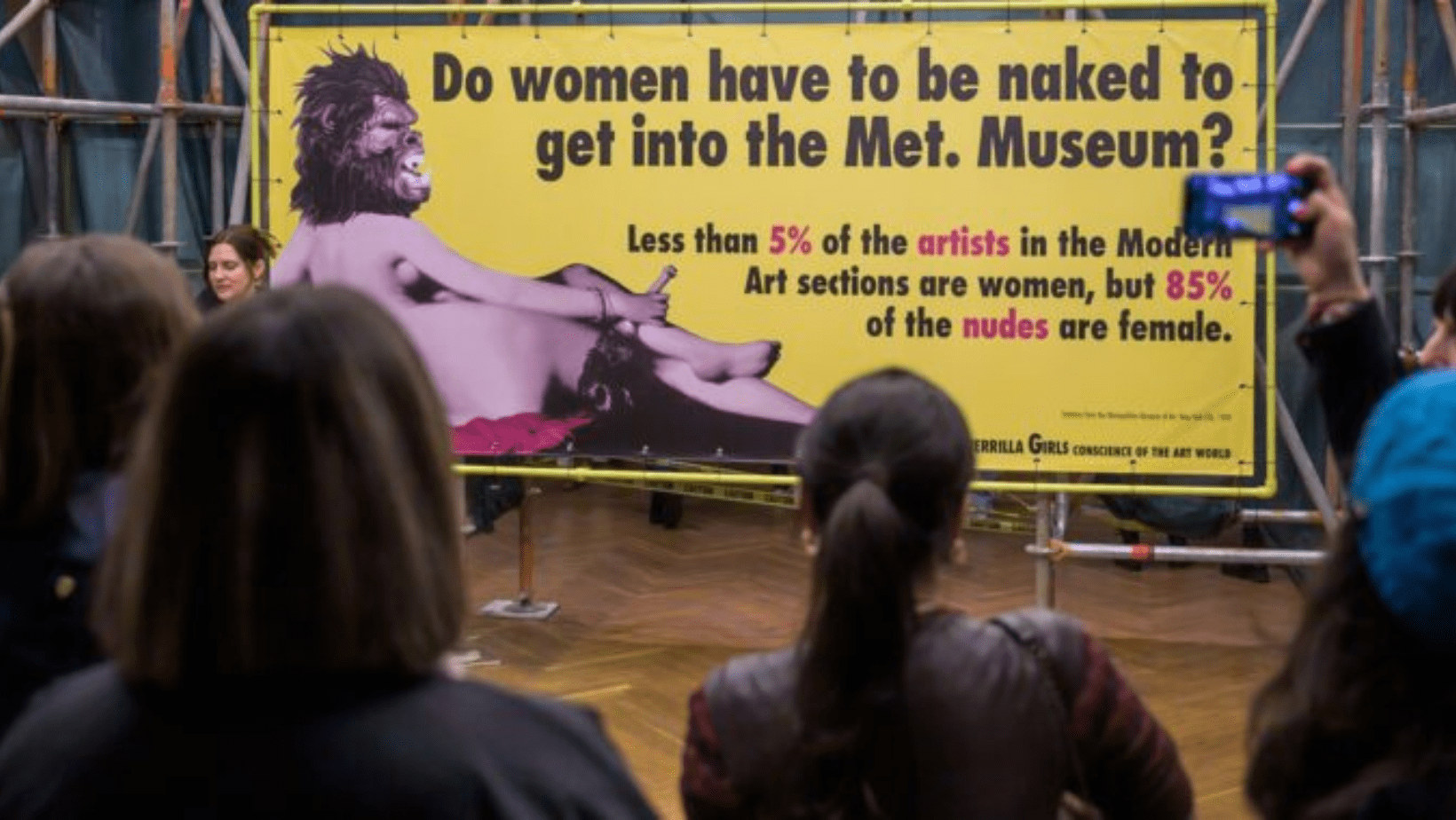

What is the significance of the Guerrilla Girls’ work in the context of the Bulgarian artistic scene?

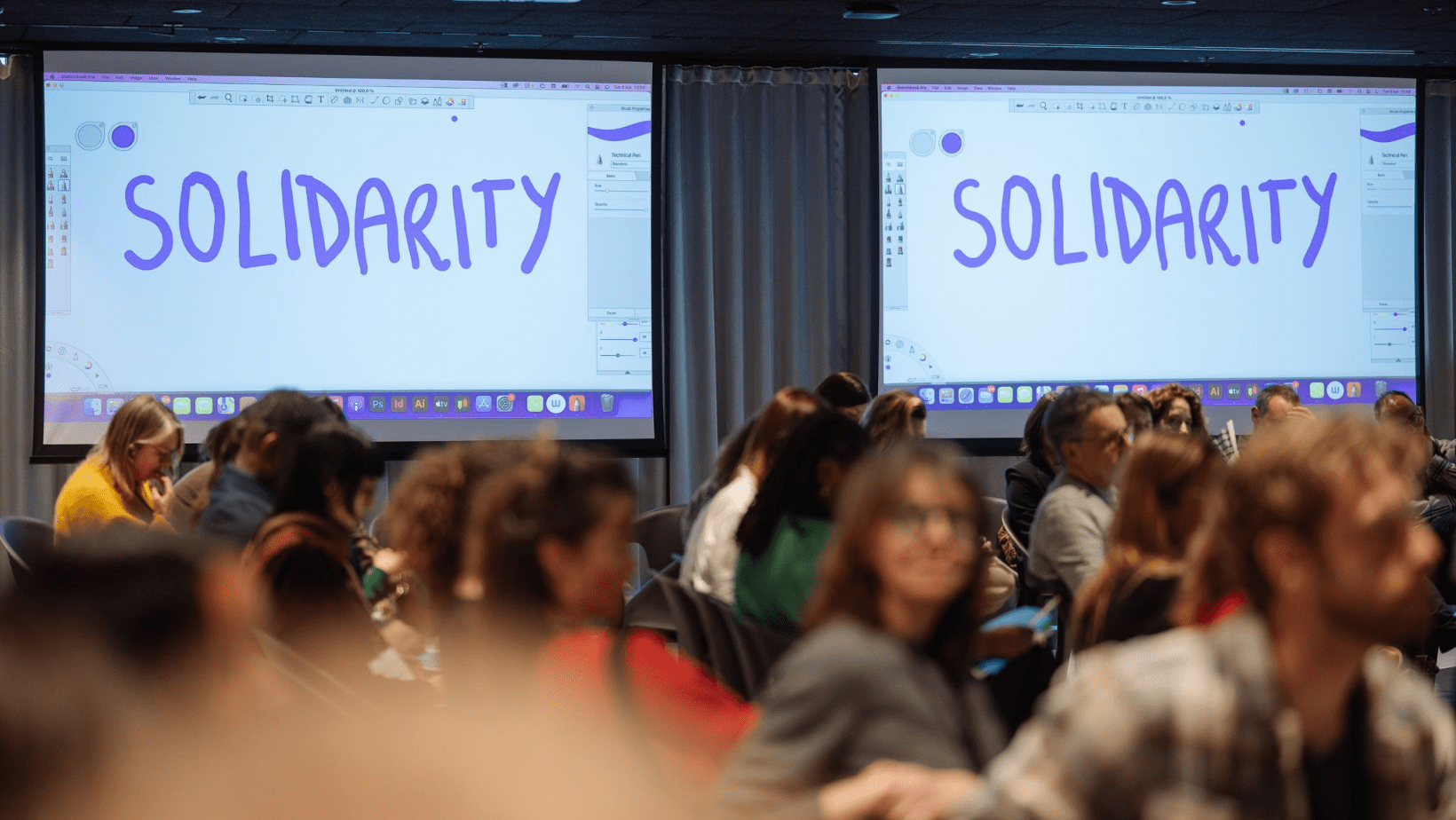

The Guerrilla Girls were an early example for us of how art can act as a form of political and social critique. In the early 1990s, as Bulgaria was undergoing dramatic societal changes, their work inspired us to understand that art can carry powerful messages and serve as a tool for activism.

As the curator of the women’s collective March 8th, I found their fight for equal representation in biennials and museum collections particularly influential. Although Bulgaria’s context was quite different, their work affirmed that artistic actions have the potential to make a real difference. Their strategy of using humor, statistics, and anonymity provided a model for how activism could enter the art space without losing its critical edge.

If you could include one work of Bulgarian art in a conversation with the work of the Guerrilla Girls, what would it be and why?

I would include my own performance Civic Position (2007), during which I knelt for three hours on Eagles’ Bridge in Sofia. The piece was inspired by a specific police operation, but it also serves as a broader metaphor for a society that brings its citizens to their knees. At the same time, it is a challenge to those who remain passive in the face of systemic oppression. Like the Guerrilla Girls, this work uses performative tactics to confront power and stimulate public discourse.

I would also mention Blood Revenge 2 (2006, Exit Art, New York; 2008, Red House, Sofia), my reenactment of a performance mythologized around Austrian artist Rudolf Schwarzkogler, who was falsely believed to have castrated himself. In Blood Revenge 2, I deconstruct this myth by inviting the audience to recreate the famous photographs from Aktion 2 and Aktion 3, while I wear a silicone dildo and enact a symbolic castration, ultimately remaining a woman without a penis. This challenges both Freudian psychology and the phallic myths embedded in art history. It’s an intervention in how female bodies and narratives are historically marginalized in performance art, echoing the Guerrilla Girls’ call to rewrite the canon.

Why is art created by women and other marginalized communities important for society and artistic circles? Has the access of these groups to the Bulgarian scene changed, and in what way?

Art has the unique ability to give voice to the silenced to confront dominant narratives, and to reflect the complexity of identity and power. Work created by women and marginalized communities not only enriches artistic discourse—it fundamentally reshapes it.

However, in the Bulgarian context, I wouldn’t equate the position of women with that of other marginalized groups. Since the socialist period, there has been a degree of institutional gender equality, and women have long participated actively in artistic life. The issue isn’t necessarily about access, but about how women’s perspectives are distinguished and validated. For example, in the March 8th group, our aim was not entry into the art world—we were already there—but to assert a distinctly feminine voice that could coexist with or challenge male-centric narratives.

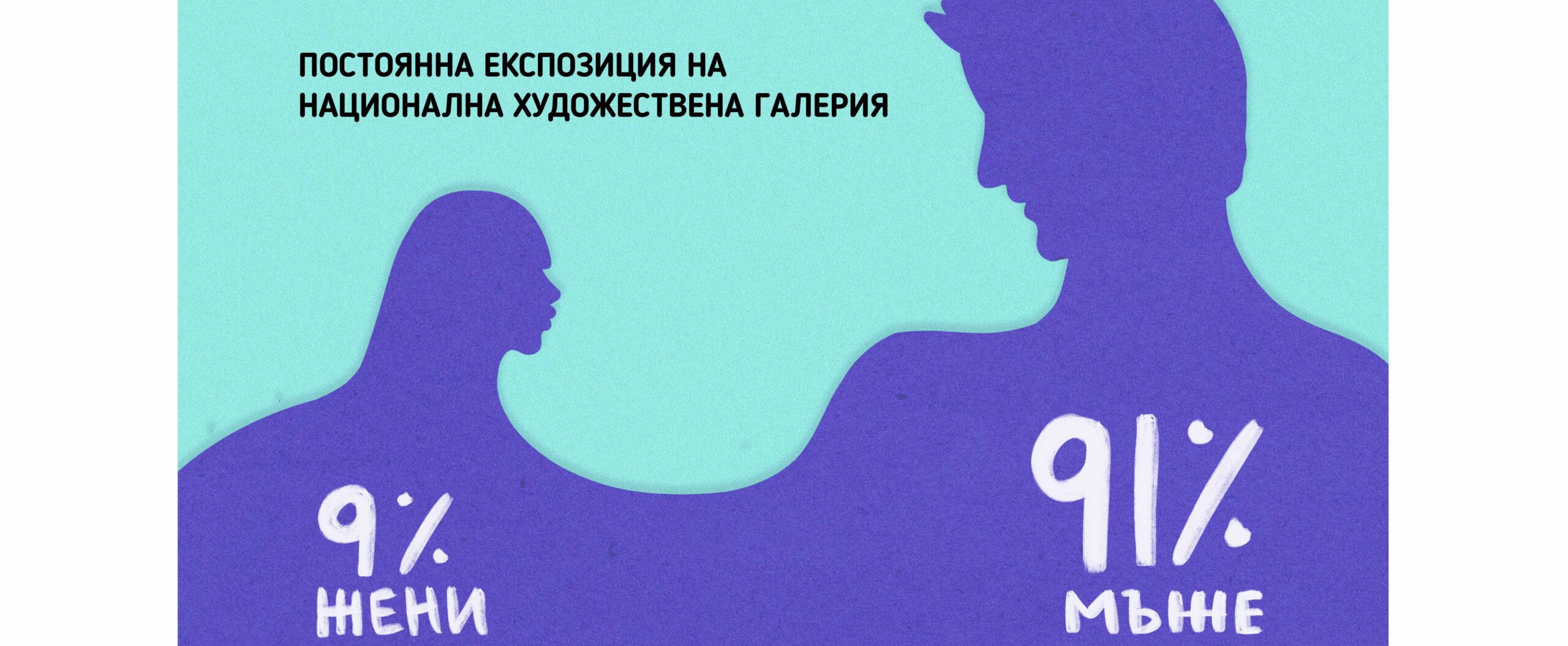

Still, I have concerns. Observing the current faculty composition at the National Academy of Arts (excluding departments like art history and restoration), it seems that female representation among lecturers is declining. This suggests a potential step backward.

It’s also important to think beyond numbers. For instance, if we consider the percentage of solo exhibitions by women in Bulgaria, they may be higher than in the U.S. But the real question is: how are women’s contributions framed? Are gender issues integrated meaningfully into broader themes, or are they isolated in “women-only” exhibitions?

There is also a lack of effort to document and historicize women’s artistic practices. How many books, films, or academic studies truly explore women’s art in Bulgaria? How do they engage with intersectionality, if at all? Similarly, the memory of women’s achievements in public life remains largely symbolic—allegories instead of real names. In contrast to the abundance of male monuments, we have very few honoring actual women.

This is why a group like the Guerrilla Girls, if adapted to the Bulgarian context, could have a much broader mission—focusing not only on art institutions, but also on women’s visibility in science, medicine, public service, and education.

Interestingly, sectors like IT in Bulgaria show strong female participation—an outcome of socialist-era policies on emancipation and technological advancement. Looking at such data through an artistic lens could help us understand and visualize women’s evolving roles across disciplines.

The Art of Behaving Badly continues until June 8, 2025, at the National Gallery / Kvadrat 500. The exhibition is part of the multi-year project of the Bulgarian Fund for Women, titled “Fund for Artistic Projects by Women Artists.”