A study into the needs and challenges of organizations protecting the rights of women, girls, and vulnerable groups initiated by the BFW revealed uneven access to resources, global crises, and the overall hostility towards gender mainstreaming continue to hamper social movements in Bulgaria

In 2021, the Bulgarian Fund for Women (BFW) initiated a nationwide sociological survey among organizations and activist groups working in women, girls and vulnerable groups’ rights and gender equality. It aimed to identify the difficulties the organizations face, so that we could better advance our vision of a just society which respects the voice and agency of each one of its members.

The study consisted of two components – a qualitative part, based on a standard Questionnaire conducted among 114 organizations representing a diverse sample in terms of size, issues, geographical scope, etc., and a qualitative part based on in-depth interviews with 39 representatives of the organizations and activist groups.

We felt such rigorous efforts were increasingly essential for our commitments to ongoing learning and knowledge transfer. As well as pinpointing recurrent challenges, the report suggests potential avenues for enhancing the Bulgarian Fund for Women’s direct and indirect impacts and aspiring towards greater sustainability. One of its merits is elucidating obstacles to involving singular CSOs (civil society organizations) or clusters of activists into a more interconnected and politically empowered civil society, a prerequisite for lasting social change. Here, we have attempted to provide a helpful synthesis of the study’s main conclusions while hoping that readers would feel intrigued to read the full report.

Uneven Access to Resources

The troubling, albeit not unexpected, overarching finding was that CSOs, grassroot groups and activists continued to operate in a precarious environment, despite grantmakers’ and donors’ best efforts. Financial uncertainty, competition for scarce resources among “newcomers” and established organizations in the field, and hostile attitudes within the community intertwined to make sustaining day-to-day operations a challenge. The quantitative survey indicated the prevalence of these issues, while the in-depth interviews with grantees illustrated how the former affect the people on the ground daily. When asked about their organization’s primary difficulties, a majority (64%) of respondents identified the scarcity of funding opportunities, a category closely related to insufficient support from the State and local municipalities (40%) and businesses (21%). Some of the primary public financing mechanisms that grantees can access, the Ministry of Justice and municipalities’ competitive calls for social service providers, are characterized by a lack of transparency, inadequate budgeting, and political volatility, among other pitfalls. To illustrate, one of the services outlined in the Ministry of Justice’s National Program for Prevention and Protection against Domestic Violence (PADVA), running a “crisis center”, is only given a uniform cost standard of slightly over BGN 13,000. Study respondents vividly described how these funds fall short of covering even basic maintenance costs, often implying “shameful” daily food allowances of around BGN 2.00 per person.

Even such insufficient funding, however, is far from guaranteed. Municipal authorities exercise discretion over delegating state-sponsored services and providing non-monetary support, such as subletting municipal buildings rent-free. The study suggests these kinds of support might be particularly difficult to access for emerging initiatives without the established track records and financial histories of larger CSOs. Actors seeking to empower marginalized groups, such as LGBTIQ+ and Roma, are also constantly at risk of backlash from conservative local representatives who might push for ceasing support. The opaque allocation of scarce resources through competitive procedures, in turn, incentivizes organizations to divert their efforts towards lobbying decision-makers through informal channels and away from collaboration and knowledge transfer with potential allies in the sector.

The contingency and time frame of the funding also entails a distinct set of difficulties. The prevalence of project-based grants, (as opposed to “core funding” that aims to keep organizations autonomous and on track to fulfill their mission) leaves little room for long-term strategic planning. The former puts additional strain on CSOs’ leadership who scramble to fill funding gaps between projects, keep their teams intact and remunerated fairly, and cope with the administrative burdens of re-applying regularly. Given this background, it was unsurprising to see that at least 15% of respondents identified the high turn-over rate as a significant challenge in their organization, while the in-depth interviews underscored further the ramifications of “burnout” among workers in the field. On the other hand, the project-based funding model appeared inconsistent with the day-to-day demands of working with vulnerable individuals, as one interviewee succinctly summarized:

“There were also difficulties because the State doesn’t seem… the institutions don’t understand the problem. That we can’t apply a piecemeal approach; we can’t work with a victim of violence for three or four months, then leave the person, then start again when we have funding. Because when you leave a person like that, their trauma is exacerbated. The person is re-traumatized.”

To summarize, both the quantitative data we collected, and the testimonials of respondents suggest the need for more flexible and timely funding alternatives which give CSOs enough breathing room to strategize.

Barriers to Activism and Advocacy

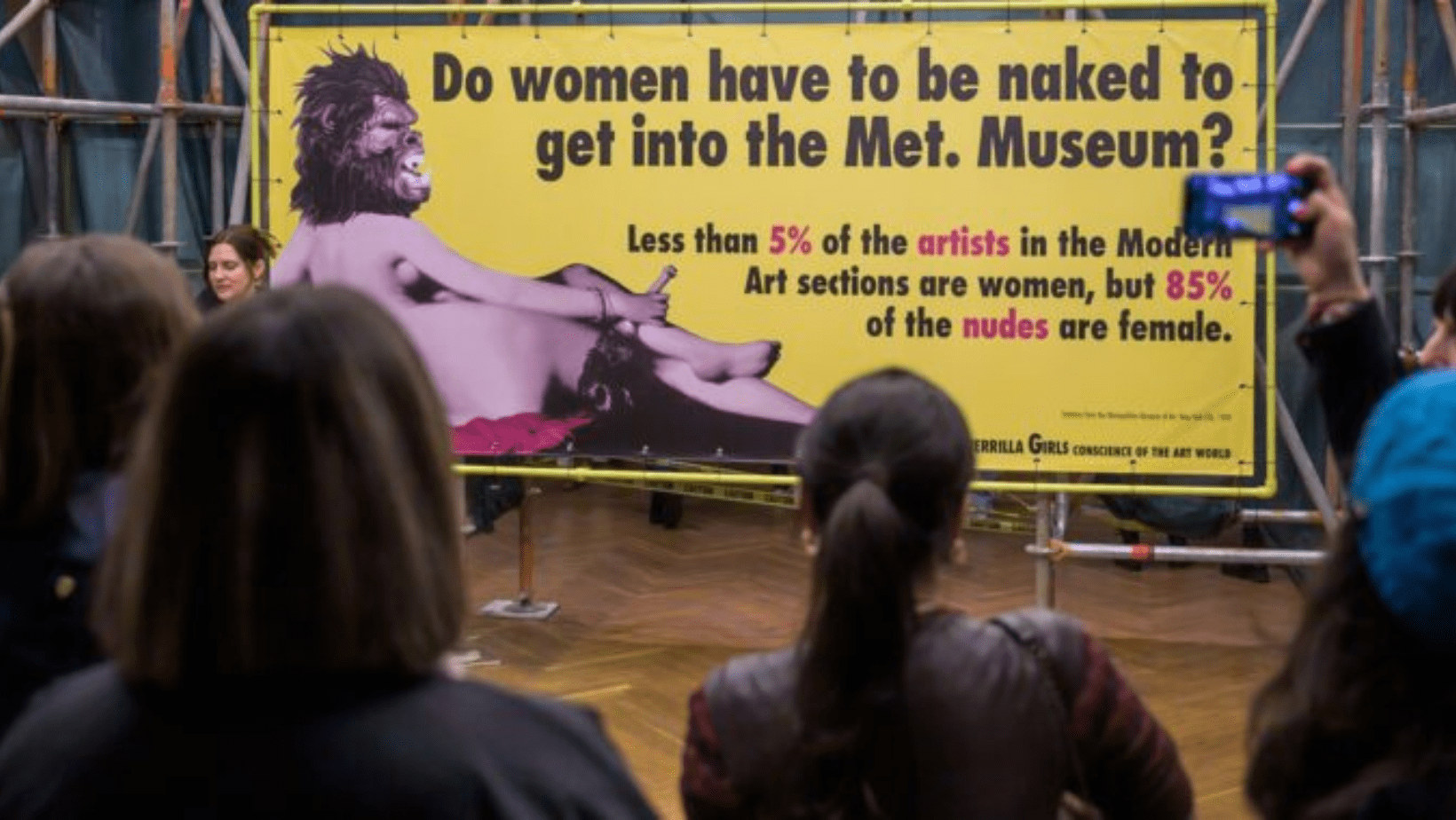

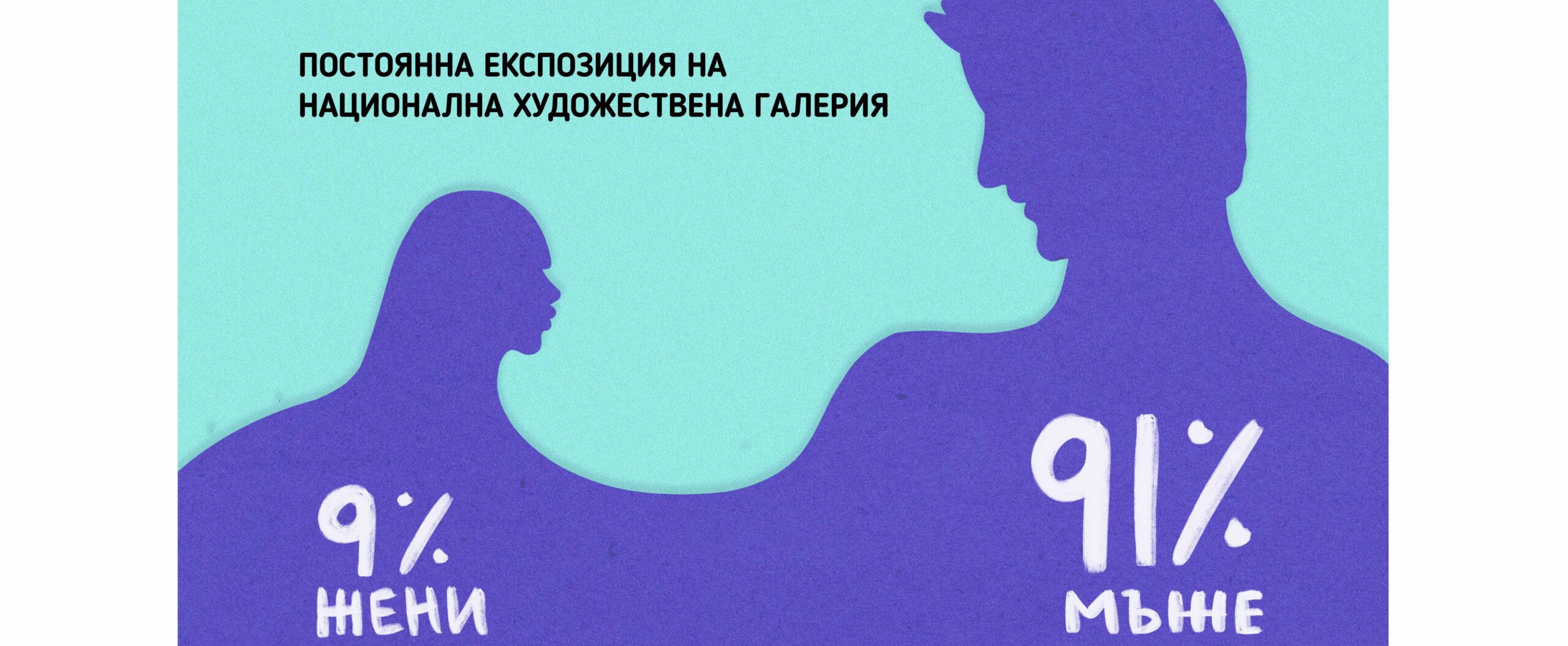

On the other hand, if left unaddressed, these structural barriers, together with the ongoing professionalization of the CSO sector would continue to hamper the overall political efficacy of civil society. Our study found that the CSO sector still consists primarily of professionals specializing in the areas of social work (46%); education (36%); law and legal services (25%), reflecting at least to an extent the beginnings of Bulgarian civil society in the wake of socialism. This background inevitably influences how our respondents frame their strategic goals and assess their accomplishments or shortcomings. Most of the former prioritized seeing an immediate difference in their beneficiaries’ lives (49%) and feeling their support was appreciated (54%) as indicative of overall success. Conversely, significantly fewer recognized successfully lobbying for legislation conducive to their mission (10%) or building lasting partnerships with political representatives (4%) as significant impact criteria. These findings suggest CSOs might feel politically disempowered or not see themselves as political subjects in the first place, but as immediate service providers. The urgency of the COVID-19 pandemic, which exacerbated beneficiaries’ vulnerabilities and needs further, also seems to have contributed to the concentration of CSOs’ efforts on basic service provision, leaving even less room for much-needed advocacy, coalition-building, and greater community engagement. At the same time, it is the latter strategic activities that could best dispel harmful gender stereotypes and curb systemic discrimination, identified as significant issues facing women by more than a third of the study’s respondents. Enhancing our partners’ advocacy and communications capacities thus emerged as a key objective for the BFW, as we strive to ensure the actors with the most extensive field experience and in-depth issue knowledge gain a say in authorities’ agenda-setting and meaningfully partake in bottom-up policymaking.

These efforts are also vital considering the study’s diagnosis of the circumscribed advocacy space that CSOs and activists must navigate after the divisive public debates on the Istanbul Convention and the National Strategy for the Child. It was telling that some respondents reported they deliberately avoid referring to “gender” issues in describing their activities – to preempt public resistance. These pragmatic choices, however, have more than linguistic implications. They risk reinforcing the invisibility of certain groups and suggesting that intertwined issues, such as gender stereotypes and domestic violence, can be de-coupled and addressed in isolation. On the other hand, some of the civic initiatives profiled in the study illustrated how seemingly narrow and identity-based political activism could relate to much broader segments of Bulgarian society. For instance, LGBTIQ+ activists’ ongoing struggle for the legalization of factual cohabitation has far-reaching implications for heterosexual couples as well. Other respondents note that framing gender stereotypes with reference to (dis)parities of unpaid labor within the household or one’s autonomy and choice of vocation seems to resonate intuitively with individuals across genders and age groups. One activist summarized the growing recognition that simplistic cultural scripts harm all parties involved as follows: “Even men get it, they understand that stereotypes of the kind that only women as mothers can provide care for the children are restrictive for them and place them in a position as if they were incapable of being fathers”.

Now what?

The concurrent hostility towards gender mainstreaming and moral outrage against domestic and gender-based violence evident in Bulgaria underscores the need to undertake more systemic sociological investigations into public attitudes in the country. Since CSOs and activists rarely can undertake such monitoring themselves, its availability is a critical prerequisite for elaborating a coherent strategy for engaging the wider public. Considering these challenges, we believe grantmaking institutions and the BFW should encourage their partners to recognize public education in the broadest sense and deliberate coalition-building as strategic objectives that are both worthwhile and viable.

We are hopeful such advocacy could prevail as, at the end of the day, it targets outdated legal and social structures, be it legislation or stereotypes, that contradict the lived experiences of individuals and families in an increasingly uncertain and dynamic world.

The full version of the report can be found here.

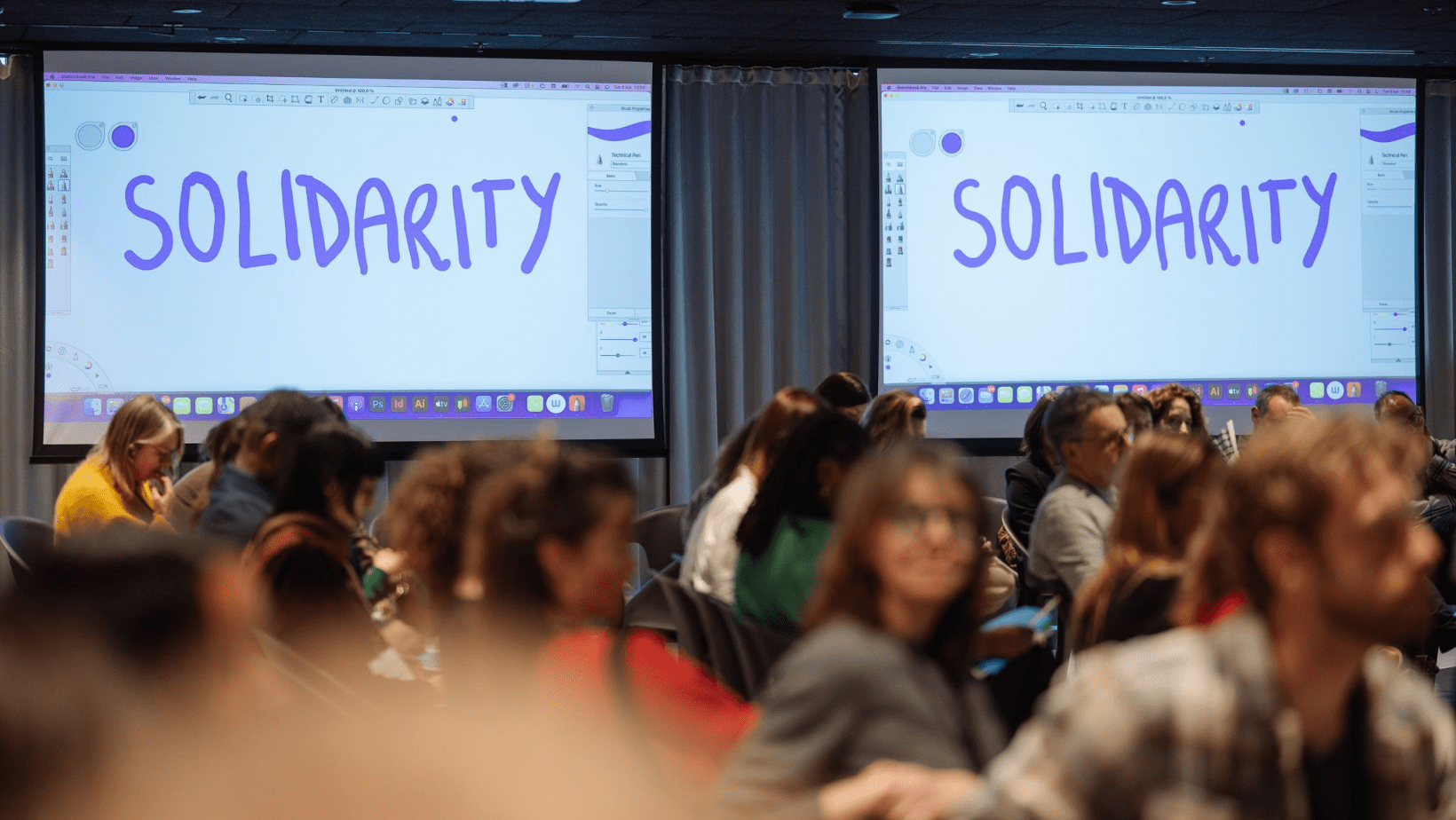

A recording from the webinar where the report was presented can be viewed here (in Bulgarian).